The irrational rationality of the markets resembles that of a chicken farmer. Feed the hen when it lays eggs. When it stops laying, slaughter it, pluck it, quarter it, and eat it.

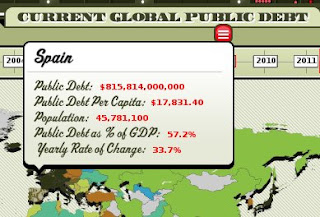

Argentine external debt 2002 0.14 billion 54% of GDP.

Spanish external debt 2011 2.3 billion 165% of GDP.

Zapatero (22 September 2010) “I believe that the debt crisis affecting Spain and the Eurozone in general has already passed.

Edward Huhg (a bonobo crossed with a neo-Malthusian chimpanzee). “If we intend to adopt a labour reform to bring about an end to the devaluation of internal competitiveness, we ought to contemplate a far more radical reform. Spanish workers should take on board the idea that they should embark on a second career after they reach 55 years of age for as long as their bodies can take it. The majority of workers over 55 have the necessary skills to form a part of a growth model possessing a high added-value, and ought to be employed in the areas which today are dominated by immigrants, accepting the same pay and conditions as they do.

The crises in Argentina and Spain have a gap of ten years between them.

In 1989, the Menem government with Domingo Cavallo, the Harvard educated Super minister of Economy, fixed the exchange rate at 1 peso to 1 US dollar in a new article of the Argentine constitution. The markets celebrated this initiative and for a while Argentina ‘enjoyed’ a veritable avalanche of cheap international credit.

The Euro was introduced into the world financial markets as a currency on 1 January 1999, the old national currencies remained as a medium of payment until 1 January 2002.)

In the case of Spain both the rhythm and volume of indebtedness were far higher than those of Argentina. After the dotcom crash the markets inflated the mother of all bubbles in the property market. Whilst Argentina took the opportunity to return to the path of growth through exports of primary materials, Euro- Spain placed itself at the head of sub-prime property speculation thanks to the market’s cheap credit available to the Spanish banking system.

The Argentine Crisis

As was the case in Spain, the fixed rate with the dollar brought enormous external debt to the Argentine economy. Financial crises followed. The Mexican crisis of 1994-5, South East Asia, Russia and Brazil. Investors took refuge in the dollar which appreciated against other currencies. Argentinian exports suffered and the suspicious markets raised interest rates for Argentina up to 20%.

At the end of the 1990’s, recession, indebtedness and cuts of every kind brought with them an unprecedented social disaster. Of a total of 36 million Argentinians, 14 million subsisted in poverty.

The new government of Fernando de la Rua came into power in October 1999. The IMF came to the rescue with a bailout (of the markets), promising a loan of $ 1000 million in return for a harsh plan of structural adjustment. In June 2000 a 35 day General Strike paralysed the country.

The money was not to be made available unless the government put into effect by decree the measures imposed by the troika of the IMF, the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank. On 23 November 2000 the government, by decree, dismantled what remained of public services, pensions were privatised, social security was deregulated, labour reforms made, the health system was privatised….

In December 2000 the troika congratulated the government on having ‘done its homework’ and announced a new ‘assistance plan’ for a total of $39 700 million to be released over three years in return for following the path of cuts.

The return of $ Cavallo (a specimen similar to de Guindos) as Minister of Economy led to rises in the stock exchange and euphoria in the markets that accepted a transformation of short-term debt to the long-term at usurious interest rates.

In return the government promised to achieve a zero deficit in 2001. A reduction in salaries (15%) and of pensions over $500 followed. Internal consumption slumped and thousands of SME’s closed down. Unemployment shot up to 25%. Tax revenue fell 11.6% in November 2001. The troika refused to release the tranches agreed in assistance plan citing the ‘timidity’ of the cuts.

The Spanish Crisis

Spain and the Euro

Under the peseta, a sharp deterioration of the commercial balance was impossible because the markets did not dare to lend too much given the risk of devaluation. The Spanish market was the private hunting ground of the local banking system which lent at high rates of interest (mortgages of 14% in accordance with its own deposits).

Graph Medium and long-term obligations issued by Spanish banks.

With the Euro as the Spanish currency, the risk of devaluation disappeared. The markets considered lending to Spanish banks to be good business so as to unleash a property bubble along the lines of those being inflated in USA, Ireland, Iceland and Eastern Europe. The German and French banks, besides participating in the US sub-prime market, threw themselves enthusiastically into the Spanish fiesta. Without their greedy participation the situation would never have reached such monstrous proportions.

Graph 1. Shares issued by Spanish banks 2.Loans as percentage of deposits.

The Spanish banking system lacked sufficient ammunition of its own (deposits of residents) to inflate the mortgage bubble and so opted to indebt itself up to the neck to the international financial system (having learnt or having been taught to issue mortgages). We are often told that the Spanish banks are not exposed to US sub-prime mortgages but the system itself has been converted into a gigantic factory churning out its own home-grown sub-prime mortgages to feed the Central European globalised finance casino.

Graph Spanish private debt as percentage of GDP

In a few years Spain became the third most privately indebted nation in the world (with a total debt of 366% of GDP). The private sector reached a level of external debt of $ 0.7 billion (310% of GDP). This made Spain a country at systemic risk.

Graph. Total debt by country

Phases of the crisis and changes of strategy

First phase. Camouflage and cosmetics

At the beginning it was believed that the crisis would be a passing event (green shoots of growth). When the bubble burst, in Spain, unlike in the majority of other countries, not a single financial body failed. Hymns of praise were sung to the health of the economy and the proverbial lack of exposure to the international financial crisis. Meanwhile in the USA, Lehman Brothers fell and other banks followed daily. The strategy employed in Spain was the following;

1. No bank or caja should be allowed to go bankrupt. Using accounting manipulations, bank balances were fiddled to present a picture of rude health. It was put about that although there were a few black sheep, the banking system as a whole was solvent.

2. Camouflage and cosmetics. The worst entities were fused with the least damaged and the whole diluted with the help of the FROB and the Deposit Guarantee Fund. The intention was to avoid at all costs any loss to creditors of the banking system, whether internal or external. In the new fused entities the toxic investments remained guaranteed by FROB under the share protection scheme. In effect FROB became the shareholder of the failed banks. FROB became indebted to the European fund, that is to say the taxpayers are now absorbing the losses of the private banks, in particular the losses of the French and German banks.

3. Plan E of Zapatero. This strategy can be summed up as giving subsidies and aid to slow down defaults and failures to pay whilst riding out the storm. Whilst in other countries property prices plummeted, in Spain property prices dropped very slowly as the banks refinanced mortgages and developers or held onto properties without auctioning them, The markets direct the orchestra and the Spanish banking system dances to the tune sporting its Sunday best although it has been left without any underwear.

Phase 2. Cuts squared

When it became clear that the crisis wasn’t passing but had come to stay, the nervous markets changed their strategy. Plan E plus camouflage and cosmetics has been a huge error. Concealing the poor condition of the banking system was achieved at the cost of exponentially increasing the deficit and public debt leaving the public sector with insufficient capacity to absorb the enormous losses and ruin of the private financial sector. Financial wizards and stress tests could no longer disguise the damage.

In addition, the nervousness of the markets was increasing the magnitude of the crisis given that the massive rise in interest rates threatened to exceed the growth of GDP, a clear indication of the bankruptcy of the country.(Greece and Ireland).

By mid-2010 the situation had become unsustainable with the danger of a domino effect coming into play, led by Greece. A rescue package was created for Greece. The exposure of the Central European banks to the PIIGS is enormous (loans to the public and private sector). Ireland owes 0.644 billion, Portugal 0.134 billion, Greece 0.166 billion and Spain 0.781 billion. (Spain needs to refinance 0.546 billion until 2013).

To avoid imminent catastrophe a European Rescue Fund was established, the EFSF, a type of terrible financial super-bazooka, that in order to be capable of 'dissuading the attacks of the markets', ought to amount to well over a million Euros. In the end its capacity for dissuasion remained doubtful as it was not even able to gather half the necessary gunpowder.

In view of the imminent débâcle (default of Spain and /or Italy), the ECB abandoned its traditional codes of practice, buying Spanish and Italian bonds by the ton, and more recently (at the end of 2011) offering a free bar to the banking system (a limited provision of credit at 1% for three years to the private banks in two rounds of 0.5 billion each). In this way the rickety banking system was able to refinance the debt to the Central European banks until 2013. In addition the ECB would acquire Spanish public debt at 5% thus relaxing the pressure of the markets and taking a rake off from the difference in interest rates.

In this way Spain has been rescued and of course intervened in by the ECB. The levers of control of the Spanish economy have been in the hands of the troika (ECB, the European Commission and the IMF) for some time. The only concerns of the troika are to minimize and /or compensate for the financial losses of the ruling gambling addicts and bubble merchants at the expense of the Spanish taxpayer and to apply shock therapy to push through privatisation of public services in the peninsula, which they intend to share out amongst the handful of multinationals which control the European hunting grounds.

In contrast to the USA, Britain, Ireland or Greece, in Spain the majority of the financial losses incurred during the property bubble (0.2 billion) have not yet been socialised. Ireland socialised the losses of its banks and was rescued. Spain, on the other hand, has been rescued without socialising the losses which have been steadily multiplying over time. The ‘financial reform’ means that Spain has to offer up accounts to the markets for the enormous hole dug by the insatiably greedy financial system. And so we have to listen to the tiresome refrain that ‘we’re all in the same boat’, that ‘we have to do our home work’ and so on ad nauseam.

De Guindos, an expert in creative accounting a la Goldman Sachs, is trying to camouflage the situation so that the socialisation of losses does not weigh upon the compromised deficit. Instead the losses are being disguised and transferred directly to public debt by the manipulation of the guarantees of the FROB, advances of the bank quotas to the Deposit Guarantee Fund etc.

As in the case of Argentina with D Cavallo, the underlying strategy of the troika and the markets lies in forcing the immediate socialisation of losses so that they appear to be flowering in the shaky balances of the banks, cutting salaries (labour reform), laying off civil servants, privatising public services, pulverising pension systems, social security, public health. Cuts on top of cuts, cuts squared. Spain has to go to jail for its debts and it looks like it will be serving a life sentence.

In Argentina, the carrot was successive rescue packages (similar to the Greek case). In the Spanish variant the carrot is the risk premium. Up goes the premium and the constitution is changed, up goes the premium and we get labour reform 2.0. A depressive budget is presented and up goes the premium the same day because the cuts to education, health and pensions are not considered sufficient. Prior to 'labour reform 2.0' the premium went up because it was considered 'timid and insufficient'.

How long are we going to go on like this? Are we going to have a Latin American style decade with a debt crisis creating terrifying percentages of crime and poverty? Under capitalism decades are not linear; either they go up or down. In 2012 we have unemployment figures over 5 million, in 2022 we will have ? million unemployed. Does anyone know what the recuperation in 2022 will look like?

Argentina. Getting out of the crisis (A clever hen)

On December 3 2001 the government imposed a bank freeze. On 12 December the seventh General Strike since the adoption of parity with the dollar was called. Pot banging, streets blocked, supermarkets looted, seven dead and hundreds injured. De la Rua declared a state of emergency. There were 4 500 detentions and 34 dead, but the social mobilisation did not stop and on 20 December de la Rua abandoned the Casa Rosa in a helicopter.

Josep Piqué. “Argentina needs to overcome, as soon as possible, the unorthodox and short-term socio-economic measures in order to recover a state of normality which would allow the recession to come to an end.”

On 2 January 2002 parity with the dollar was abandoned. The mobilisations and protests continued and the new government feared social explosion more than the threats of the IMF, the USA and the markets. The IMF threatened to stop lending any more assistance and gave Argentina a year to repay its debt, although later it reconsidered and announced a loan of $ 710 million for the government to finance the provincial government debt (civil servants were receiving their salaries in debt vouchers issued by the provincial government). In exchange Dualde promised more cuts, Unemployment shot up to 25%..

Meanwhile the devaluation of the peso (30%) punished the foreign investors in the privatised public services who were demanding increases of between 40% and 260% in tariffs. On the other hand prices of imported products shot up. Social mobilisation continued, now under the catchphrase ‘Que se vayan todos’ (Get out the lot of you). On 26 June 2000, after a picket line was attacked resulting in two new deaths, Dualde resigned. In December 2002 more than 100 000 people paraded in Buenos Aires demanding a popular assembly to change the roots of the economic system,

On 25 May N Kirschner announced an increase of 50% in the minimum wage and expansive budgets to stimulate demand and economic activity. A little later he summoned the markets and agreed a 75% write off of the debt. The Argentinian economy recovered speedily and strengthened thanks to the stab to the global property bubble. Spain. Exit from the crisis

Those of you who know, please put down your plan in the comments section.

RUSSIA CAPITALISM II Lee Raymond (CEO of Exxon-Mobil 1993-2005). “We are not an American company and I do not take decisions based on what is good for the USA. Anders Anslud. “The biggest story of corruption in human history” John Browne (former Managing Director of BP). The problem is not the lack of laws but their selective application. This is what creates the feeling of anarchy. Whilst legalistic bureaucratic processes continue to be the distinctive hallmark of Russia, one never knows if someone is going to turn a blind eye or if the laws were correctly applied. Russian capitalism 1.0 Capitalism was introduced into Russia in the XIX Century. We are dealing with an already mature form of capitalism which had already experienced its first industrial revolution. As in the USA and other countries, it was capitalism compatible with the strengthening of the nation state. It was installed and prospered with the creation of a national industrial nucleus, protected against external competition by tariff barriers. It was also capitalism with advanced monopolist characteristics in which trusts and holdings dominated the panorama and forced states to engage in imperialist wars. Metalworkers at the end of XIX Century One of its leaders was Sergei Witte, the minister in charge of supervising the building of the trans-Siberian railway. A follower of Fredrich List, he wanted a strongly protected domestic industry for Russia and defended the passing of protectionist legislation. He also promoted the modernisation of the education system (business schools) to improve technical training in the country and in 1887, passed a law limiting working hours in factories. His attempts to reform agriculture brought him up against the nobility and he fell from power in 1903. The first capitalist penetration into Russia was a long and complex historical process of assault and remodelling of the state, which in the end failed after the disaster of World War I and the resistance of the population to being turned into cannon fodder. Russian Capitalism 2.0 The capitalism which was reintroduced into Russia at the end of the XX Century had very different characteristics. In the new trans-national monopolist capitalism, nation states no longer constituted the base and principal lever of the corporations, but were mere accessories, interchangeable and to a certain extent unnecessary. For capitalism 2.0 the USSR constituted a vast and rich communal territory to loot which had up until then resisted its advances. In contrast to the first failed experiment, the second capitalist conquest of the USSR by ‘shock therapies’ and ‘express’ privatisation, was a lightening process of infection, dismemberment and de-structuring, which lasted less than five years. Russia was almost instantly converted into a corrupt mafia economy, fuel dependent and on the periphery of trans-national monopoly capitalism. There was no ‘transition’ in any sense of the word. Transnational monopoly capitalism does not require a nation state to operate. The institutional juridical framework, laws and public regulations, the social contract and national magna cartas are often a waste of time and an obstacle to business competitiveness and appropriation of added value. An opportunity for neoliberalism to loot on such a scale doesn’t arise every day. The reconquest of Russia was designed and planned to make it the biggest capitalist orgy ever seen. First loot, dismantle, privatise, steal, accumulate…there is plenty of time later for the tedious business of administration, and the construction of laws and rules which neoliberal capitalism finds so abhorrent. Day and night capitalism 2.0 picked through the ruins of the soviet state without providing any alternative institutional juridical framework. The grotesque privatisation theft of public wealth without the existence of even the minimal legal framework or juridical security led to a lightening escalation, enormous and unprecedented, of criminal activity given the legal loopholes and lack of economic regulation. The dismantling of institutions which protected public property was not followed up with an alternative which would protect private property and contracts. The obvious answer in the face of the institutional vacuum and the lack of security and legal protection was to go in search of the support and protection from Russian organised crime which evolved ‘spontaneously’ to become the principal bulwark of the private capitalist economy, the defender of illegally acquired public property, the guarantor of the validity of financial and commercial contracts, becoming a sort of arbitrage system in the shadows which sustained the new capitalist order and is able to dictate and force the adherence to basic norms so as to reduce uncertainty in exchange and business. In the 1990’s more than 70% of the contracts made were signed outside the legal framework. The growth in the number of criminal gangs involved in business violence was spectacular. In 1991 there were 952 criminal groups, in 1992, 4 300 in 1993, 5 691. The explosive emergence of organised crime during the first years of the 1990’s can be considered an informal institutional response to protect property rights and contracts, the necessary third leg of the stool for the correct functioning of the new neoliberal order. Financial-Industrial Groups FIG’s Terminal neoliberal bubble capitalism is profoundly short-termist. Financial speculation dominates and takes first place in front of the real economy which is increasingly forced to play a secondary role as the base of the hyper-leveraged financial casino. It is its absolute irresponsibility for the criminal consequences of its attacks, bubbles and bursts, swindles, shock therapies, labour reforms, constitutional reforms, thefts of shares, salaries pensions and savings… that makes it the worst system of social organisation ever devised. As the results of its envestida are unavoidable the degeneration of Russian capitalism into a mafia certainly fails to meet all the criteria hoped for in the field of law and order to consolidate the penetration of transnational monopolies and financial capital. One alternative to a ‘failed state’ is the creation of clans which try to usurp the functions which would otherwise be carried out by a consolidated state. In the absence of valid institutions social groups tend to reorganise themselves gathering in tribal structures, clans or groups following a code of criminal obedience such as the mafias. The planet is filling up with substitute structures or alternatives to the nation state model which work in parallel to the state the majority of its functions. Something like this has taken place in Russia; No new capitalist state administration has been constructed above the erased slate of the Soviet system which is capable of operating in the trustworthy or functional fashion required by transnational monopolist capital. After ten years of chaos during which the Russian people were reduced to the cruellest misery and lost more than ten million souls what has emerged is a corrupt and necessary pseudostate which shares power between an amalgamation of mafia clans which interact and share out business via ‘Financial Industrial Groups.’ The emergence of the FIG’s During the first round of privatisation (1993 to 94) 16 500 public companies (two thirds of the total) were privatised through a system of vouchers or certificates shared between the directors, the workers and the Russian citizens (capitalism of the people). The freeing of prices in January 1992 set off a huge inflation which depreciated savings deposits in the banks by 99%. The companies, now without state contracts, were unable to continue paying their workers. The majority of the ‘peoples capitalists’ found themselves obliged to sell their vouchers cheaply to the few who had ready money. By 1994 three quarters of the companies had passed into the private hands of corrupt officials and gangsters. People’s capitalism had come to an end. Appropriation, hoarding, dismemberment and the sharing out of public shares by kleptocratic criminal groups at the centre of decision making was the tonic for the privatisation process. For this reason Yeltsin shelled the parliament in 1993, a body which had shown itself too fond of popular capitalism. Potanin, Chubais and other Yeltsin cronies, now freed from parliamentary control, designed a plan in the spring and summer of 1995 by which the Russian government would receive loans from the Russian bank guaranteed by shares in the main strategic industries (petrol, energy, gold, diamonds, nickel). In the event of the government failing to repay the loans, the banks would have the right to auction the shares of the companies. The loans for shares plan has been cited as the largest robbery in history. From the beginning it was a planned operation of the theft of shares, organised by and for a group of future oligarchs, drawn from a small circle of corrupt officials in collusion with organised crime. As was foreseen from the very beginning, the Russian government was unable to repay the loans by the set date. They were placed on auction where those participating were individuals or companies controlled by the same banks. In all cases the share packages were picked up for a small sum above the derisory starting price. The corrupt and penniless government requested loans from the banks (controlled by mafias and oligarchs) guaranteeing the loans with monopolies and public companies. Onexim Bank, controlled by V. Potanin, one of designers of the plan, picked up 34% of Norilsk Nickel (producer of a fifth of the nickel and two-fifths of the platinum in the world) for $170,1 million (the 0,1 represented the plus which was paid on top of the starting price of the auction. In 2003 its price was estimated at $53 000 million. Other companies auctioned were Sibneft (oil) acquired for $100, 3 million, Sidanko (oil) .for $130 million, Yukos, (one of the biggest oil producers in the world) which was acquired by the bank Menatep owned by Mijail Khordorkovski for $159 million. After the division of the spoils seven ‘bankers’ had obtained control of 50% of the Russian economy. Once the cake was cut up (Yukos , Sibneft etc.) a privileged group of oligarchs was created, Potanin,,,,,,,,,,,,,M Prokhorov with enormous resources to support the political and economic course laid down by Yeltsin (re-election in 1996). Consolidation of the FIG’s At the end of the 90’s organised crime had achieved substantial control over the privatised businesses thanks to its role as the arbitrator and guarantor of the system, resolving corporate disputes, ensuring the payments of debts and fulfilment of contracts. They also began to provide loans to entrepreneurs (start ups) and businesses, exchanging loans for shares and ended up controlling many of their clients. After privatisation a few monopolist, mafia-dependent, industrial structures, with highly concentrated capital completely dominated the social and economic panorama in Russia. R.M Gates, the former director of the CIA, estimated in 2001 that two-thirds of commerce, 80% of banking, a good part of the stock exchange and 150 large public corporations were controlled by organised crime. 40% of the GNP was in the hands of the mafia in connivance with corruption. After privatisation, Financial Industrial Groups immediately sprung up, amalgams of monopolies and banks which claimed to be Russian versions of Japanese keiretsu or South Korean chaebol. In reality these business structures worked as clans linked to specific groups of organised crime. The principal FIG’s were Inkombank Group, Most-Bank Group, SBS-Agro Group, Oneximbank Group, Rossiyski Kredit Group etc. By the mid-90’s there were 27 large FIG’s that concentrated 446 corporations (65 banks) and had more than 2 million employees. Many of these FIG’s remained under the control of organised crime from the time of their foundation. On the behalf of the principal FIG’s, there formed a cloud of minor FIG’s on the bank-corporation model in each and every sector of the economy with the banks operating as financial managers (money laundering) and as a source of information at the service of criminal groups. At the head of each group there are businesses of a monopolist character joined with one or several banks. At the second level are grouped secondary firms and a third level of subsidiaries. A key element of the group is a structured lobbying organisation which seeks to promote its interests to the state bodies. The management and control as well as the appropriation of the major part of the income is concentrated in a small number of individuals who possess between 30 and 50% of the shares of the group. These FIG’s administer and control the social infrastructure (clinics, outpatient centres, kindergartens, housing, Trades Unions) of their employees, operating as true clans. A telling feature of the structure of the clan is that the banks can retain the wages of the employees for months to use in speculation which can bring in (or not) additional income for the clan. It is also not unusual to divert the wages owed to support electoral campaigns of candidates who are favourable to the clans. It is a complicated system of mutual financial connections between businesses, banks and regional or federal government agencies and above all the personal connections of the clan. In this way the clan structures constitute the basis of political power. The intersection of interests between both spheres of power is often complex. Some clans support various parties simultaneously and many parties have the support of various clans. What gives these clans solidity is their wide links with organised crime. Although there is a certain degree of formal economic competition between them the struggle is largely informal. The important things are personal connections, pacts and agreements to divide up the markets and spheres of influence, the establishment of ‘rules’, pacts of competition etc. apart from the usual criminal practices of blackmail, bribery murders etc. It is a battle between forces trying to regulate the market. Each clan tries to regulate the market in its favour and the strongest clan, not the most competitive producer, is the one that wins. In no other case in history has organised crime achieved such economic and political power as in the neo-capitalist countries of the former Soviet Union. So much corruption at the highest level can have no other result than to create a perfect symbiotic relationship between the official administration and organised crime. The Russians inhabit a neoliberal capitalist medium in which illegality is most rewarded and sought after and in which organised crime has taken over the function of control and government of society. The arbitration of Putin and stabilisation The rise of Putin took place during the period of hyper-depression, with GNP in free-fall, 80% of the population in poverty, President Yeltsin drunken, kleptomaniac and ill, the organised crime groups entrenched in the majority of the economic sectors warring amongst one another and chilling levels of corruption. Putin embodied arbitration as the sine qua non to maintain the new status quo. The new state reorganised by Putin and his associates works as the arbitrator of the post-Soviet clan structure by establishing itself as the most powerful clan. With scarcely any tangible income, the Russian state was dissolving like a sugar lump. At the behest of the markets and the international agencies Putin recovered for the state part of the income from energy which was being hijacked by some of the mafia clans (forced bankruptcy and nationalisation of Yukos, the arrest of Mikhail Khordorkovsky and the Gazprom monopoly) and ensured himself of the backing of the majority of the oligarchs (Genaddy Timchenko, Vladimir Yakunin, Yurly Kovalchuk, Sergey Chemezov) He also renationalised shares in the hands of foreign multinationals. Royal Dutch Shell and its Japanese associates found themselves obliged to cede their holdings in the promising joint venture, Sakhalin II, to exploit the rich oil and gas fields. BP were compelled to cede the rich gas field of Kovykta (in Eastern Siberia) to Gazprom. In 2003 the state controlled only 10% of oil production. In 2008 44% of oil production had returned to the pubic sector which also controlled 85% of gas production. Has Putin created a vertical command structure of the Prussian or Soviet type? A sort of restoration of authority? The reality is more prosaic. Putin’s state is Putin’s clan. What there is in all instances of the Russian mafia state is a complex web of client loyalties in which everyone works frenetically for their own ends and in which some cover or protect others or share the tasks (for example the police and army extort and receive protection moneyfrom small businesses whilst the secret services -FSB- have exclusive rights over the large corporations. There is no political rivalry between a supposed liberal wing (Mendev would be the standard bearer) and a statist wing (sioviki or pro-Putin). The reality behind the thick curtains of the press and the TV is not an ideological struggle but a shadowy illegal war between a dozen mafia clans which use every type of trick to control the maximum portion of income and cash flows which the system produces. It is competition between competitors with the same purposes and objectives. A common objective is the appropriation of a business by a rival clan (raiderstvo) which is a well documented phenomenon in Russia. Very often the manipulation and abuse of apparently legitimate mechanisms such as bankruptcy or criminal trials are the preferred methods to gain control of (steal) businesses. Raiderstvo could not exist without the direct support and connivance of the authorities, the prosecutors, the police and the courts. The same Russian state authorities have brought about a multitude of acquisitions of private businesses using similar means. More than 100 000 businessmen are imprisoned at present, and one in six businessmen report having been victims of criminal attack. The raiders falsify the power of attorney and illegally transfer corporate shares or start frivolous judicial actions and pay the judges to award the claimants millions of dollars in damages. Plots to force bankruptcy, judicial plots, falsification of land deeds….. are all commonly used tactics. To lose your place in this network could mean ruin and prison and this also goes for the highest ranking members. The apparent 'stability' has more to do with the enormous danger inherent in leaving someone else in charge or leaving a department than anything else. The anti-prevarication laws, courts and judges exist to destroy and liquidate anyone who falls out of favour with the mafia customer networks. If there is any type of hierarchy or verticality in Russia today it is impunity. If you are a member of the FBS (secret service) you can also work as a hit man given that your official job ensures you total impunity in your second job. In this manner, the peculiar stabilisation of Putin, the depreciation of the rouble and the meteoric rise in prices of primary materials and fossil fuels pulled the country out of hyper-depression and the abyss of a failed state. Between 1999 and 2008 Russian GNP grew at an average rate of 8%. In 2004 The GNP had regained the level of 1991. Once the initial predatory euphoria had passed and after the de-structuring, dismantling and dismembering and sharing out of the pubic shares had taken place the markets and the multinationals are not totally pleased with the present situation given the arrogant precipitation and criminal greed. A few doses of corruption, illicit trafficking, prevarication and fiscal fraud sit fairly well with the current multinational capitalist system. Business schools teach that a certain amount of informality rejuvenates and makes capitalism more dynamic. Failed states and criminal capitalism, however, do not sit too well with the majority of businesses. This is the present dilemma facing the stabilisation achieved by Putin. Russia was on the point of turning into a (nuclear) failed state at the end of the 90’s. Putin’s stabilisation avoided disaster but converted Russia into a criminal capitalist state, diverting a good part of the shares and flows of income from the habitual channels of accumulation of neoliberal monopoly capitalism. The Russian Matrix Neoliberal politicians and economists confirm that Russia and the old eastern bloc countries have been ‘normalised’ thanks to the advice and guidance of the IMF and other neoliberal agencies (G7). In any case the neoliberal ‘transitionology’ accuses the soviet legacy for the strange deformities of present Russian capitalism. The normalisation of Russia is explained in the following way: 1. The transition has not been too catastrophic a process. The depression was fairly mild (more of a recession) and the economy rapidly recovered (by 2003 GNP had recuperated the level of 1989). 2. What was to blame, in any case, was not Yeltsin’s rapid liberalisation and the shock therapies of the IMF and other neoliberal agencies (G7), but the nature of the soviet system itself, which caused its collapse and subsequent depression. The rapid liberalisation led to greater ills being avoided. 3. The escalation of organised crime together with galloping corruption was the heritage of the soviet system. 4. These countries have crossed over from the shadow of an authoritarian centrally planned economy to a virtuous democratic system of free enterprise in which consumer demand governs the supply beneath the rule of law and in which wages and income are fixed by negotiation in accordance with the law of supply and demand. 5. Criminality has been reducing over time. The oligarchs and kleptocrats who looted and appropriated the soviet patrimony have been transformed, in the same way as the robber barons John Rockefeller and JP Morgan, into first class entrepreneurial businessmen, true motors of westernisation. 6. The old countries of the Soviet Union have been converted into economies with large middle classes advancing rapidly towards the status of developed western economies. 1. The transition has not been too catastrophic a process. The depression was fairly mild (more of a recession) and the economy rapidly recovered. The post-Soviet hyper-depression (1990-98) was much deeper than the American Great Depression and cost the lives of 10 million Russians. Sovietologists used to accuse the soviet statistics of being exaggerated (the tendency of the planned system to provide good production results). CIA statistics recalculated the data presented between 1913 and 1987 to show a median growth of 4% per year in GNP in roubles (1917-1987, 4,7 % in dollars). Angus Maddison, one of the specialists in the Soviet economy who most cut back the official statistics, published his results in 2003 which showed figures of a drop in GNP of 45% between 1989 and 1998 and an unemployment level of 25%. The reality of the hyper-depression was not only a matter of numbers. Sociological studies show an unprecedented increase in deaths (3,4 million died prematurely between 1990 and 1998) caused by privation and misery in the absence of wars, pandemics or other extraordinary factors. The hyper-depression shown by Maddison’s figures was real and lethal. The addendum to the hyper-depresson was the neoliberal bubble of 1996-1998 and the subsequent crash. The Russian administration was financing its growing expenditure with loans from foreign countries. The foreign investors acquired Russian debt in exchange for high interest rates. Solely to be able to pay the interest on these, the Russian government began to ask for loans in the form of short-term bonds (GKO’s). To be able to attract nervous investors they had to put the interest higher and higher. In May 1997 they paid interest rates of over 150% per year. After the re-election of Yeltsin the government allowed the purchase of GKO’s by foreigners. Chase Manhattan, US, Credit Suisse, First Boston, Republic Bank… threw themselves into the hunt for GKO’s. In order to pay the interest the government issued further GKO’s. It was a typical Ponzi pyramid scheme. The new loans paid the interest on the previous ones. The foreign and Russian participants in the GKO casino made fortunes whilst the orgy lasted. The GKO’s were so lucrative that the Russian banks themselves invested in them instead of making commercial loans. On October 6 1997 the principal Russian stock exchange index reached its historic maximum (571 points, a year later it would fall to 37 points) making it the strongest emergent financial market on the planet. But the Russian dream lasted only a short time. With the hangover of the Asian financial crisis of 1997 the investors began to withdraw silently, converting their rouble shares into dollars. Nevertheless, in spite of the warning signs the markets believed that Russia was too ‘nuclear’ to fail. Bank of America, Credit Suisse, First Boston Corp., Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs and Citibank had lent huge sums to the speculators. In May 1998 Larry Summers convinced Clinton to obtain an extraordinary contribution of $10 000 million from Congress to the IMF to ‘save capitalism in Russia’. In spite of this Goldman Sachs took out a subscription of Eurobonds worth $1,025 million which were fully subscribed. In August the Moscow stock exchange was forced close a few times because of falls of over 10%. Liquidity disappeared from the market. The Russian government declared itself bankrupt, announced a unilateral suspension of payment of GKO’s and allowed the rouble to float. Bank deposits were frozen by decree- two months of corralito. In less than 24 hours the sudden fall of the rouble made prices shoot up - and debit cards ceased to function. Dozens of banks closed and disappeared (only a handful of banks controlled by the mafia and the oligarchs were rescued by the Russian Central Bank). In a few days the savings of the Russian citizens evaporated. Unable to withdraw their savings the citizens could only watch helplessly as their value diminished with the rouble. Those that had not lost their job found that they could not receive their wages. When they were finally paid, their wages had lost two-thirds of their value (the average fall was between $160 and $55 per month) and the number of Russians living below the official poverty line passed 40%. GNP in 1997 had been $422.000 million. In 1998 it scarcely reached $132 000 million, a fall of 74%. • Share prices fell 90% in a year. The rouble fell 75%. Inflation shot up. In the face of financial and monetary collapse the Russians resorted to barter. The teachers in Voronezh were paid their salaries in tomb stones. The ‘transition’ was a catastrophic process without any palliative. In the 90’s the direction of globalisation directed by the IMF-World Bank tandem led to the conversion of the Second World (the old Soviet bloc) to the Third World, with the greatest and fastest increase in poverty registered in history, from 14 million to 170 million in less than four years. The hyperdepression generated a veritable demographic disaster, unprecedented in times of peace. An average of a million Russians a year were wiped off the demographic statistics from 1991 until the middle of the first decade of XXI Century. The Russian demographic tragedy Graph 2. What was to blame, in any case, was not Yeltsin’s rapid liberalisation and the shock therapies of the IMF and other neoliberal agencies (G7), but the nature of the soviet system itself which caused its collapse and subsequent depression. The rapid liberalisation led to greater ills being avoided. The USSR had demonstrated its great capacity for recuperation from disaster on various occasions (1917-21 and 1940-45). In addition other centrally planned economies evolved into capitalist markets without creating a depression. What caused the hyperdepression was the unbridled greed and short-termism of neoliberalism which directed and planned the famous shock therapies. Washington was always in the know about about the most serious criminal activities.. Clinton allowed the Wall Street financiers to direct American policy with respect to the capitalist transition of the former Soviet bloc. The standard bearer of the whole operation was the ‘Russian Privatization Center’ which had close links to Harvard University. The centre received funds and loans from the US Treasury, the IMF, the European Bank of Reconstruction and development, the European Union, Germany and Japan which totalled over $400 000 million. The Clinton and Gore administration did not hesitate to hush up the scandals, criminal conspiracies, frauds, robberies and money laundering in their own back yard - the Bank of New York was used to launder money for Russian organised crime - ignoring CIA information which reported the situation, alleging the fear of a communist opposition to Yeltsin. All the information of corruption, fraud and penetration of organised crime were disregarded and the IMF and the US Treasury continued supporting and enriching the new Russian ‘capitalists’, that is to say the mafia, and large-scale corruption continued with the increasing bubble. Those principally responsible for American policy towards the transition were Vice-President Al Gore and the then Treasury functionary and now high economic advisor to Obama and inventor of the ‘Bad Bank’, Lawrence Summers. These two referred to the notorious and corrupt oligarchs Boris Nemtsov and A. Chubais (their intimate personal friends) unblushingly as the ‘economic dream team’ of Russia. 3 The escalation of organised crime together with galloping corruption. Was this due to the Soviet heritage? During the Soviet period there did exist organised mafias which supplied illegal imported goods to the nomenclature. Their role and importance was, however, absolutely marginal. The normal nexus between the economic, social and political breakdown and the advance of organised crime was increased by lightening privatisations and the dismantling of structures which protected public property without any alternative being substituted which would protect private property and contracts. The alternative to the institutional vacuum and the lack of security and judicial control was to look for protection and support from organised crime which evolved ‘spontaneously’ to become the principal support of the new private capitalist economy, the defender of dubiously acquired private property and the shadow guarantor of the validity of financial and commercial contracts. Organised crime became institutionalised as the only structure capable of dictating and enforcing the basic rules necessary to reduce uncertainty in the trade and business of the new capitalist order. This situation has not changed substantially. A certain natural evolution in the ways of extracting income by increasing the range and sophistication of extortion methods has taken place. In 2009 Russia suffered the consequences of the financial crash of 2008 resulting in a fall of GNP of 8%. The ‘official’ crime figures recorded an escalation of crimes (the Ministry of the Interior reported the commission of 492 000 economic crimes, an increase of receiving bribes of 13% in relation to the previous year and losses of $33.000 million as a result of these crimes). Price Waterhouse Coopers, the external auditor, concluded that Russia led the ranking in economic crime (a category which included uncompensated appropriation, accounting fraud, corruption, money laundering, tax fraud, price manipulations and cartels). According to the audit at least 71% of Russian businesses had suffered some sort of criminal attention from the kryshka ( ‘the roof’, a euphemism for the protection offered by organised crime, a figure which was 13% higher than in 2007) with a notable return to more violent methods of extortion. 4. These countries have crossed over from the shadow of an authoritarian centrally planned economy to a virtuous democratic system of free enterprise in which consumer demand governs the supply beneath the rule of law and in which wages and income are fixed by negotiation in accordance with the law of supply and demand. The virtue of the new neoliberal system was based on an unequal redistribution of the income and wealth on an enormous scale. Multimillionaires sprung up like mushrooms whilst the hyperdepression (a drop of GNP between 1991-1995 of 34% and 70% in 1998) led to mass pauperisation and an unprecedented social crisis (accompanied by an accelerated gap between rich and poor). Crime figures and murders doubled whilst life expectancy dropped by 5 years. By the end of 1992 40% of the pensioners were receiving less than half the subsistence level. After the debacle of the 90’s economic recovery did not bring with it political or economic liberalisation but in fact the opposite. The gagging of the media Russia is the third most dangerous country in the world for journalists (after Iraq and Algeria). Putin dominated all the TV channels and the great majority of the newspapers. Only the internet escaped but the FSB are working hard to establish control of the net. 85% of Russians report that the television is their main source of information. At the beginning of his term of office Putin clashed with Boris Berezovsky and seized control of ORT (the chain with the largest audience) converting it into his largest mouthpiece (Channel One). He then forced the oligarch Vladimir Gusinski to abandon the country placing his TV chain (NTV) in the hands of Gazprom. In 2003 Putin dominated or completely controlled the media and the ‘news’ was changed into something similar to the propaganda of Franco’s NODOS. Russian TV does not reflect reality or spontaneity (all programmes and shows are censored and there is no live coverage) but creates a disconnected parallel universe. The Kommerzant newspaper (the property of Berezovsky) maintained an independent point of view and was valued for its information on business and politics. The newspaper was bought by an affiliate of Gazprom in 2006. Izvestiya had already been bought by Gazprom in 2005 and stopped informing the public, turning into a trashy tabloid. Other publications absorbed by the Putin clan are Nevavisimaya gazeta, Novye Izvestiya, Moskovskiye novosti, Segodnya, Itogi, Obschaya Gazeta, Komsomolskaya Pravda… The few publications remaining outside the Putin orbit are regional papers or very small. In the internet the Putin clan is rapidly regaining lost ground. Live Journal, the American server which hosts the most popular blogs among the 300 000 Russian bloggers, was acquired in 2006 by Anton Nosik, a wealthy capitalist residing in the USA with close links to the Kremlin. In February 2008 the ‘law of communication media’ was passed that tried to muzzle the internet. In April 2008 an even more restrictive law was passed reinforcing the previous legislation. At the end of 2008 Rinet the best known and oldest Russian server, used by many dissident bloggers, was forced to close following the persecution by the secret police that seized all the servers in order to investigate them. Trades Unions? The ‘official’ unions are similar to the old Francoist vertical unions. They play a client role, subordinate to the clan or Financial-Industrial Group to which they belong and act as distributors of the profits made by the FIG’s. The cowardice of the official unions is so great that over the last few years new alternative unions have emerged and developed (funded only by members) which have become relatively strongly entrenched amongst miners, port workers steel workers and workers in the multinationals, in spite of repeated cases of reprisals, torture and assassinations carried out by gunmen contracted by the bosses. These ‘free’ unions attack the anti-labour legislation (fruit of successive neoliberal ‘labour reforms’) which allow little margin for protest and organisation and have organised illegal strikes against multinationals, Nestle, Leroy Merlin (megastores), and against RUSAL (the largest aluminium producer in the world in the hands of the oligarch Oleg Deripaska), obtaining considerable wage rises. 5 Criminality has been reducing over time. The oligarchs and kleptocrats who looted and appropriated the soviet patrimony have been transformed, in the same way as the robber barons John Rockefeller and JP Morgan, into first class entrepreneurial businessmen, true motors of westernisation. The crime and corruption figures have not dropped at all during the 20 years following the beginning of the transition but completely the opposite. Corruption and crime have become wedded to Russian capitalism (some writers in Wikipedia refer to the Russian federation as a mafia state). The endemic and institutionalised corruption in the Russian education system from kindergarten to the top universities is a thermometer adjusted to the global criminal corruption which envelopes Russian society. The oligarchs and new rich send their children to study abroad. Private education institutes in Britain and Switzerland, at all educational levels, receive substantial fees from their welcome Russian clients. For the Russian on the street, however, the new capitalist education system is paid. Payment, however is not confined to registration fees and education-related costs but bribery of all types is the norm. The system of ‘informal ‘payments is generalised in all areas. For the students, the normality of bribery prepares them for a society in which bribery and corruption reign. Families pay between $2000 and $4000 in bribes to get their children into kindergartens (demand exceeds supply and there are waiting lists for over three years). In order to study in the nearest schools, to get good marks, to pass the course, to get university entrance (to get a good mark costs between $3 500 and $5 500), to be able to get into a good university, to be able ‘repeat’ an examination (the poorly paid teachers set difficult exams to oblige their pupils to repeat in order to get an informal supplement which enables them to subsist. In an article in The Guardian at the end of 2010, referring to telegrams about Russia published by Wikileaks, the following characteristics of the functioning of the state are described The Russian spies use the services of mafia bosses to facilitate arms dealing. The police, the spy agencies and the prosecutors control and operate extortion rings to ‘protect’ their clients (businessmen, politicians, gangsters…) in return for juicy premiums. Bribes work as a parallel tax flow and are channelled directly into the pockets of the police and the security services (FSB). Investigators of the Russian mafias in Spain have compiled an extensive list of Russian prosecutors, military and politicians implicated in the networks of organised crime. To avoid military service, register a new company, buy an apartment, get a school or university place, pass an exam, be declared innocent of criminal charges be they valid or false, receive medical treatment… all require bribes. The plague of bribes is endemic, inflating the cost of transactions by up to 50% from buying arms to constructing a motorway. With time, what has happened is not the decriminalising of the Russian society and economy, but on one hand the forced adaptation to the system on the part of the businessmen, workers, clients and suppliers, which makes them accustomed to operate in an environment of crime and corruption (adapt or die), and on the other hand a natural evolution and sophistication of corrupt criminal practices. There is no dual system (with a dominant formal economy versus a residual informal economy) but both sectors connive and intermingle with a profound predominance and preponderance of crime, and ‘formality ‘ or ‘normality’ is a mere façade. In fact organised crime offers businessmen a wide range of services: protection from extortion by other groups, defence from legal harassment by corrupt state agencies, protection of property, payment of debts, help with Customs, risk assessments by banking services controlled by the mafia (these banks are very useful in obtaining information for criminal enterprises - transfers and credit cards- and are crucial for transferring money or money laundering. Russia lies at the lower end of the 22 countries evaluated in the Transparency International Bribe Payers Index and in a position lower than China. The TIBPI index tries to measure corporate corruption in place of public corruption which is measured in Corruption Perception Index on a global scale, and which in 2010 placed Russia at number 154 of the 178 countries with a figure of 2,1 on a scale of 1 to 10. The old countries of the Soviet Union have been converted into economies with large middle classes advancing rapidly towards the status of developed western economies. According to Medvedev, the middle classes are the key instrument in the objective of modernising the politics and economics of Russia. According to a study by Rosgosstrakh (a public insurance company) in 2007, the group which registered the largest increase in income were those who earned between $125 000 and $250 000 per year. There were 200 000 households (0,37% of the total) with annual incomes of over a million dollars. Only 6,7% of Russians earn over $930 a year. The average per capita income is $279 and the average wage is $420 (the average agricultural wage is under $190 and that of teachers is $273) therefore even at the decisive moment of economic recovery the number of possible members of the middle class was extremely small. The per capita statistics do not include any reference to inequality, mortality, illness, the tremendous environmental degradation, the deterioration of infrastructure and public services. The rich live in exclusive neighbourhoods protected by electrified fences (like Rublyovo-Unpenskove Road, on the outskirts of Moscow) although the great majority of their most favoured gated communities lie outside of Russia. This new capitalist class feels insecure in its own country. It has its families living in London or Paris, its children studying at Oxford or Cambridge and its money in Switzerland or the Cayman Islands. Economic growth has been and will continue to be enormously disproportionately in favour of the super-rich. In neoliberal circumstances, as is occurring in the USA and the EU, the middle classes are a sector in danger of extinction.

Financial Times. 10/02/2010: "Si los países europeos "periféricos" eligen una aproximación keynesiana para salir de la crisis, serán masacrados por los mercados."

España está pillada de lleno en lo que los economistas llaman la trampa "moneda-crecimiento-deuda”, un fenómeno que ya empieza a ser un clásico de la globalización financiera.

Familias, empresas y estados son tentados con el señuelo engañoso de condiciones inmejorables de financiación. Se organizan explosivas burbujas financieras aquí y allá con booms espectaculares de las bolsas donde unos pocos iniciados obtienen ganancias espectaculares. Cuando las burbujas estallan el FMI se encarga de proteger la retirada a tiempo de los principales agentes que incluso sacan buenos réditos especulando a la baja.

La hoja de ruta empezó tras la crisis del petróleo poniendo en la mesa de juego los petrodólares reciclados y los fondos de pensiones. Los países en desarrollo se convirtieron de golpe en países "emergentes" y empezaron a sucederse burbujas por todo el planeta dejando una estela de miseria y perplejidad tras los ineludibles cracs. Finalmente han sido los propios países desarrollados los que han acabado siendo pasto de la globalización financiera.

España abandonó su moneda y cedió su instrumental de política monetaria al Banco Central Europeo. Desde el 2002 el euro sustituyó totalmente a la peseta. La fortaleza del euro ha ido en detrimento de la capacidad exportadora española, sin embargo la confianza en la estabilidad monetaria y los bajos tipos de interés en la zona generaron una entrada neta de capitales en el tropel especulativo inmobiliario de la última burbuja que revitalizaron el crecimiento del PIB al tiempo que aumentaba el déficit comercial y se disparaba endeudamiento exterior hasta cotas estratosféricas.

El equivalente a la caída de las exportaciones (materias primas) argentinas a finales de los 90 ha sido en España el batacazo inmobiliario, la depresión y la caída subsiguiente de los ingresos por turismo. Como en Argentina, el endeudamiento privado (banca, inmobiliarias) se está convirtiendo en público. Como en el caso argentino los inversores están ya formando enjambres, virtuales nubes de langostas, especulando con una posible bancarrota española. La Comisión y el FMI, al servicio de la banca acreedora centroeuropea, han tomado el mando y están condicionado el mantenimiento del suministro del suero crediticio para mantener con vida a la torpedeada economía española a una "devaluación interna" (drásticos recortes del gasto público, devaluación del sistema de pensiones, devaluación de la seguridad social y de la sanidad pública, devaluación de la educación pública, anorexia del sector público y dosis letales de flexibilización laboral, ...).

Tal como viene operando la trampa MCD, mientras se mantenga inamovible el cerrojo monetario (la permanencia en el €), decrecimiento y endeudamiento se retroalimentan. La vuelta al equilibrio es imposible. La magnitud de la crisis global ha precipitado hacia la trampa a diversos países europeos de la zona euro (PIIGS) y amenaza muchos más. Grecia, el peón a sacrificar, está sirviendo de conejillo de indias para experimentar una medicina cuyos efectos secundarios podrían afectar la continuidad del euro en su conjunto. El paciente principal sin embargo, en la salita de espera, es España. Las desreguladas instituciones financieras siguen amplificando la magnitud de las crisis apostando a la baja en macro operaciones encubiertas fuera de todo control.

Se trata de una espiral en la que los inversores se lanzan sobre los bonos de los países centrales (Alemania, Francia, Holanda, ...) huyendo de la comprometida deuda de los países de la periferia que ven como se disparan sus costes financieros hasta niveles inaceptables que no hacen más que empeorar su ya difícil situación financiera.

Las multinacionales empiezan a contemplar la alternativa de una euro-Europa reducida a los pocos países que aún sean capaces de mantenerse en la ratio déficit/PIB permitida.

Todo apunta a que con un endeudamiento (privado + público) de merecido podium mundial, un sistema financiero plagado de cajas zombi en la UVI pública, cerca de 5 millones de parados y la economía sumergiéndose en picado, la "devaluación interna" se traduzca, como en el caso argentino, en menos demanda, menos consumo y menos ingresos por impuestos. A medida que vayan venciendo los términos de las obligaciones privadas (bancos y cajas) y públicas (estado, autonomías) y con "los mercados" huyendo de cualquier clase de papel ibérico, las desfondadas administraciones central y autonómicas no tendrán otra manera de seguir pagando sus gastos corrientes que emitiendo monedas ad-hoc como en la época de la guerra civil. Los “patacones” de Buenos Aires podrían muy bien traducirse en “barcinones” para una de las nuevas veguerías proyectadas en la hiper-endeudada Cataluña.

La expulsión de los PIIGS de la zona euro seguramente se producirá por sorpresa y de forma conjunta pare evitar un pánico bancario. El factor sorpresa (sin previo aviso excepto para los ricos con buenos contactos) es clave en una operación de este tipo. Un día nos levantaremos de la cama con la noticia de que a última hora del día anterior el euro dejó de ser la moneda del Reino de España y los depósitos bancarios quedarán bloqueados para convertirse en pesetas al cambio que decidan las autoridades. En un santiamén el valor de los ahorros de los incautos depositantes sufrirá un recorte drástico e irrecuperable.

Argentina se libró finalmente de la trampa porqué renunció a la paridad con el dólar (equivalente a salir del €) y se declaró en suspensión de pagos, introdujo controles sobre las salida de capitales, elevó los impuestos sobre las exportaciones y el sector financiero y la burbuja inmobiliaria relanzó la demanda mundial de materias primas. No parece que vaya a ser este el caso para España a medida que se profundiza y generaliza la Depresión Permanente. La recuperación de la experiencia traumática argentina no tendrá un equivalente a corto o medio plazo en la península Ibérica.

Los estados desfondados por los rescates de la crisis bancaria y el descalabro económico subsiguiente se ven sometidos ahora al chantaje financiero de la economía casino. Se trata de una estrategia de choque para imponer drásticos programas de desmantelamiento en pública subasta del Estado social de un amplitud aún no vista en el norte desarrollado. Se trata de convertir a los PIIGS y a los países del Este europeo en economías "de peaje" donde habrá que pagar por usar una carretera, ir al CAP, llevar los hijos al cole o tener vigilancia en tu calle. Una estrategia capitalista de choque que se va a imponer implacablemente en tanto no encuentre una respuesta socialista de choque.

Durante los años 90 Argentina, el alumno más fiel y mimado del FMI, experimentaba un "milagro económico". Los inversores extranjeros invirtieron miles de millones de dólares en el país, la inflación era inferior a la de los EEUU y el país registraba uno de los crecimientos más altos de América Latina.

En dos años la economía argentina se hundió. La crisis afectó a todos los niveles de la sociedad con una pauperación en masa relámpago.

1989. Menem es elegido presidente y nombra a Domingo Carvallo como ministro de economía. Se lanza un programa de ajuste estructural que incluye una reforma impositiva en favor de los ricos, la privatización de lo mejor del sector público, liberalización del comercio exterior, desregulación en todos los ámbitos y una paridad fija del peso argentino respecto al dólar.

1 de abril de 1991. El Congreso argentino aprueba la Ley de Convertibilidad garantizando la conversión peso-dólar de 1 a 1. Cada peso en circulación estaría basado en un dólar y la política monetaria quedaba supeditada a esta ley.

1991-1994. Argentina registra un fuerte crecimiento económico.

1995. La crisis financiera mexicana y la devaluación de diciembre de 1994 del peso mexicano lleva a un pánico financiero y una retirada masiva de fondos de los países emergentes (efecto Tequila). El PIB argentino cae (- 2,8%)

1996-97. Argentina vuelve a crecer expectacularmente (5,5% en 1996, 8,1% en 1997) pero el déficit comercial y el endeudamiento se disparan.

1998. En la estela de la crisis asiática de 1997, crisis financiera en Rusia y Brasil. Argentina entra en recesión en el tercer cuatrimestre. El paro se dispara.

Enero de 1999. Brasil devalúa su moneda afectando de lleno a las exportaciones argentinas (la exportación a su vecino representa más del 30%)

Septiembre de 1999. El Congreso argentino aprueba la Ley de Responsabilidad Fiscal, que plantea una gran reducción del gasto público, tanto a nivel federal como provincial.

Diciembre de 1999. De la Rua pide ayuda al FMI.

Marzo de 2000. El FMI acuerda la concesión de un préstamo de 7,200 millones de $ condicionado a un estricto ajuste fiscal.

10 de mayo de 2000. El FMI recomienda un recorte drástico del gasto público. El gobierno anuncia un recorte del gasto público de mil millones de dólares con la esperanza de que la "responsabilidad fiscal" devolverá la confianza de los inversores. El ajuste consiste principalmente en recortes y retrasos en las pensiones y en los sueldos de los funcionarios y la anulación de los subsidios por desempleo. El PIB del 2000 cae un 5%.

Muchos analistas atribuyen la severidad de la crisis a que el gobierno, aleccionado por el FMI, evitó abandonar la paridad con el dólar hasta que ya fue demasiado tarde.

Marzo de 2001. Domingo Cavallo, el ministro de Menem que diseñó la paridad con el dólar, vuelve a ocupar la cartera de economía. Se procede a una reestructuración de la deuda externa cambiando deuda a corto por deuda a largo a interés más alto. Cavallo no duda en saquear el fondo de pensiones públicas para pagar un vencimiento de 3.500 millones de deuda.

Julio de 2001. Cavallo anuncia un plan de déficit cero. Los sindicatos convocan una huelga general. El congreso aprueba la "Ley de déficit cero" y el FMI acuerda un nuevo préstamo que desaparece casi inmediatamente fugándose hacia paraísos fiscales.

Octubre de 1001. Los inversores se niegan a refinanciar la deuda pública. Las administraciones locales y el mismo gobierno central empiezan a emitir pseudo-moneda (Lecop, Patacones, Porteno, Quebracho, ....). Se trata de títulos de deuda pública emitidos a nominales pequeños que se usan para pagar a los funcionarios y para las transacciones corrientes.

Octubre de 1001. Los inversores se niegan a refinanciar la deuda pública. Las administraciones locales y el mismo gobierno central empiezan a emitir pseudo-moneda (Lecop, Patacones, Porteno, Quebracho, ....). Se trata de títulos de deuda pública emitidos a nominales pequeños que se usan para pagar a los funcionarios y para las transacciones corrientes.

Noviembre de 2001. Argentina propone una nueva reestructuración de su deuda que implica en realidad una suspensión de pagos. Retiradas masivas de depósitos de los bancos. Las reservas en el Banco Central disminuyen en 2.000 millones en un solo día. De la Rua impone la limitación de retirar un máximo de 1000 $ al mes (corralito).

Diciembre de 2001. El día 5 de diciembre el FMI se niega a acordar un préstamo al gobierno con lo que ya no puede hacer frente a sus obligaciones y Argentina se declaró en bancarrota el día 7. El paro llegaba al 18%. Los sindicatos declaran la 8ª huelga general desde 1999 para el día 13. Asaltos a supermercados. Continuos levantamientos populares en muchas ciudades (28 muertos). El gobierno declaró el Estado de Sitio. Domingo Cavallo dimitió. La crisis política acabó con tres presidente en un mes. El FOREX cerró durante tres semanas.

Técnicamente los economistas afirman que la economía argentina estaba deslizándose hacia una trampa "Moneda-Crecimiento-Deuda" a finales de los 90. El tipo de cambio sobrevaluado impide las exportaciones, la economía se estanca. Si Argentina abandonara la paridad con respecto al dólar sufriría represalias financieras con retiradas masivas de fondos. La caída del PIB provoca el crecimiento de la deuda. Si se reduce el gasto público para disminuir la deuda se frena más el crecimiento. Es como un inestable taburete de tres patas; recortas una para equilibrarlo y se desequilibra por el otro lado.

La relación fija entre el peso y el $ favoreció la entrada de capital extranjero. El PIB aumentó (de una media del - 0,7% entre 1980-1990 a un media del 4,7% entre 1991-99). La inflación quedó contenida (4% a partir de 1994, 1% a partir de 1996) y se produjo una notable caída de los tipos de interés internos que, no obstante, siguieron siendo mayores que los intenacionales, atrayendo así entradas de fondos (entre 1994-2000, LIBOR 5-6%, tipo de interés argentino 8-12%).

La apertura financiera fue total tras la supresión de las restricciones a la movilidad del capital y la supresión de las restricciones a la penetración de la banca extranjera. Se permitió la libre emisión bancaria de títulos negociables en moneda extranjera, supresión de las trabas a la entrada de capital extranjero en compañías de seguros y fondos de pensiones. La masiva privatización de empresas estatales (el gobierno ingresó 16,000 millones de $ entre 1991 y 1998) y la misma liberalización del sistema financiero favoreció la entrada de un considerable volumen de inversión directa atraída por las jugosas oportunidades a precios de saldo. La disparidad en los tipos de interés atrajo inversiones en cartera (aprovechar la revalorización de la bolsa y préstamos bancarios).

El régimen monetario y la apertura financiera explicarían no sólo la crisis sino también el crecimiento espectacular a partir de l991. Argentina se convirtió en el alumno predilecto del FMI, el mejor solista de la globalización bajo la experta batuta del FMI.

Las entradas netas de capital pasaron de un montante de 6.402 millones de $ en 1992 a 10.449 millones en 1998. La financiación externa neta pasó del -3,1% del PIB en 1990 al 2,1% del PIB en 1995 y al 5,9% en 1998. Estas entradas de capital ( 170.000 millones entre 1992 y 1998) contribuyeron a la revalorización de la moneda argentina y a la acumulación de deuda externa (61.337 millones de $ en 1991 - un 26% del PIB - , 141.371 millones de $ en 1998 - un 51,1% del PIB - ).

El deterioro de la competitividad comercial debido a la apreciación de la moneda junto con el descenso del precio de las materias primas (en 1999, el 68,3$ de las exportaciones argentinas eran materias primas y derivados) hizo entrar la economía en recesión mientras se disparaba el déficit de la balanza por cuenta corriente (exportaciones menos importaciones y pagos por intereses).

El parón del crecimiento, el desequilibrio en la balanza de pagos y el aumento de la deuda externa provocaron la desconfianza de los inversores. Como en el caso de la crisis asiática, un enjambre cada vez más voluminoso de inversores empezaron a apostar por la quiebra del Estado Argentino mientras que se producía una fuerte fuga de capitales y se hacía imposible refinanciar la deuda externa. La suspensión de pagos estaba cantada. Falto de ingresos el gobierno y las administraciones locales se vieron en la necesidad de emitir pseudo-moneda para pagar sus gastos corrientes y los sueldos de sus funcionarios. (Patacones en Buenos Aires, Lecor en Córdoba, Petrom en Mendoza, ...)

Los recortes del gasto público y las medidas de flexibilizacion laboral (Ley de responsabilidad fiscal y Ley de déficit cero, ...) no hicieron más que acentuar la recesión aumentando el paro y disminuyendo los ingresos fiscales. El PIB acumulaba una caída del 10% a finales del 2002.

Cuando finalmente se declaró la suspensión de pagos el pánico se apoderó de los depositantes previendo un cambio en la política monetaria y se lanzaron en tropel a sacar sus depósitos en dólares de los bancos (unos bancos que, como en el caso español, estaban teóricamente bien supervisados y capitalizados). El gobierno declaró “el corralito” (máximo 250 $/semana) para evitar la fuga de capitales. Finalmente se abandonaría la paridad con el dólar dejando flotar al peso que a las pocas semanas cotizaba a 2,4 pesos/dólar. Los pequeños ahorradores experimentaron una masiva destrucción de sus derechos de propiedad al ser obligados a convertir sus secuestrados depósitos en dólares a pesos devaluados.

Cuando Kirchner ganó las elecciones a la presidencia en 2003, heredaba un país devastado. Reunió a los acreedores del país y les propuso pagar solamente entre un 25 y un 30% de lo adeudado. O aceptaban reestructurar la deuda según estas condiciones o seguirían sin cobrar un dólar. A regañadientes los tenedores de bonos argentinos, después de patalear en las oficinas del FMI, acabaron doblegándose a la propuesta. Esto permitió dedicar fondos a la recuperación económica. Se introdujo controles sobre las salida de capitales y se elevaron los impuestos sobre las exportaciones y el sector financiero. El PIB argentino, que había caído un 10% en 2002, recuperó un 8% en 2003. Argentina fue tachada como indeseable por los mercados financieros internacionales, sin embargo a partir de este momento empezó una recuperación económica que le permitió pagar sin atosigamiento la totalidad de su deuda al FMI en 2005 (y el espaldarazo financiero que representó la compra por parte de Venezuela de 2.400 millones de dólares en bonos argentinos). Según la CEPAL, entre 2002 y 2009 la tasa de pobreza cayó desde el 45% al 11%.

Argentina creció a un ritmo del 10% anual desde 2004 a 2008 aprovechando la subida del precio mundial de las materias primas, pero una razón fundamental del crecimiento fue que los recursos financieros fueron invertidos en la economía en lugar de pagar los servicios de la deuda. El peso argentino quedó desligado del dólar. Se establecieron controles sobre los precios internos, tasas sobre las importaciones y exportaciones, topes sobre los beneficios de las empresas, crecimiento en el gasto público, etc. Se rechazó de plano la entrada en la Zona de Libre Cambio de las Américas, impulsada por Washington y que hubiera precipitado a las economías sudamericanas hacia el abismo criminal en el que se devana el fallido estado de México tras su pertenencia a la zona de librecambio con EEUU y Canadá.

Argentina paso de ser el mejor alumno del neoliberalismo a ser la bestia negra que fomenta los "default" (suspensiones de pagos soberanas), los controles de capitales, las empresas dirigidas por los propios trabajadores, ...

Pero los mercados difícilmente sueltan prenda. Hay fondos de inversión especializados en la carroña (vulture funds), que husmean tras las suspensiones de pagos y las quiebras para adquirir, a precios de saldo, los bonos de deuda de los quebrados. Su recompensa está en la paciencia (y el acierto) con la que esperan que la sangre vuelva a fluir por las venas de los cadáveres para llevarlos de inmediato a los tribunales exigiendo la devolución del nominal que figura en sus polvorientos títulos.

En el caso argentino, el fondo hedge carroñero NML (con base en las islas Caymán y subsidiario de Elliott Associates, un vulture fund norteamericano famoso por cuadruplicar su inversión ganando un caso contra la deuda de Perú en los 90) hace años que litiga contra Argentina por un enorme paquete de bonos de deuda que adquirió por la mitad del nominal. NML se apoya en un lobby norteamericano – American Tassk Force Argentina – que presiona para que se tomen represalias contra Argentina por no pagar a los carroñeros.

Nordelta, multinacionales y materias primas

Pero Argentina ya no es lo que era. "La recuperación" ha ido en beneficio de los cada vez más ricos que han decidido irse a vivir a Nordelta, una ciudad segura, privado-vigilada, vallada y alambrada, con campos de golf exclusivos y puertos deportivos, con escuelas y hospitales de lujo, ciudad de ensueño exclusiva para ricos evasores fiscales que se expatrian de la Argentina que explotan y sólo pagan contribuciones a su nueva patria privada.

Las desigualdad social sigue siendo un lastre. Más del 36% de la población activa trabaja en el sector informal y la economía ha continuado concentrándose en manos de unas pocas compañías transnacionales. El cultivo de soja transgénica (18 millones de Ha, más de la mitad de la superficie cultivada del país), está en manos de unas pocas empresas agroindustriales y la mayoría de los grandes servicios públicos siguen en manos de los monopolios privados transnacionales que se los apropiaron, a precios de saldo, en la época de Menem. La economía argentina depende demasiado de la exportación de materias primas, un sector sometido enteramente a la especulación financiera que podría estallar muy pronto (la base de la pirámide especulativa ha sido el impresionante plan de obras públicas lanzado por China para combatir la recesión, plan que, a todas luces grandioso, no va a conseguir sacar al conjunto del planeta de la Depresión Permanente.

Links:

Tom Lewis: Argentina's revolt

A. de la Torre, ... : Argentina's Financial Crisis. EL Yeyati, SL Schmukler - unpublished, World Bank, 2002 - econ.umn.edu