Spanish

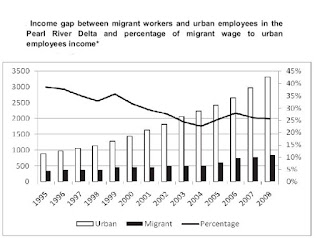

Du Runsheng: "For two decades since 1980 there has been almost no real increase in wages of rural migrant workers (Nong Gong Min) in coastal areas despite the rapid growth of China as a major economic linchpin of the global economy"

David Coates (theoretical netizen new capitalism): "Modern globalization is a process based less on the proliferation of computers than in the proliferation of proletarians"

Kam Wing Chan: "Alarmingly, the gap between the total population living in cities and the number of those with urban residence registration (urban Hukou) has increased as the country progressed. That gap represents the expansion of many people living in the city but not belonging to the city (Nong Min Gong)"

There are an estimated 274 million rural migrant workers in China, representing more than one third of the working population. Migrant workers have been the engine of spectacular economic growth in China over the past three decades.

Migrant rural workers - Nong Min Gong -, are workers with a rural Hukou (household registration) who are employed in a place of urban work. However, many of them have not even been born in rural areas. Many have grown or even born in the city but according to the Hukou system they retain the stigma of Nong Min Gong from their parents.

Chinese State and multinational capital have contributed to keeping this great mass of proletarians as marginalized persons subject to institutionalized discrimination, as if they were undocumented foreigners in their own country.

Chinese capitalism has created a system of production relations that is more efficient and brutal than most. The formidable escalation of China as the most competitive industrial power in the world, has been largely achieved thanks to a highly efficient exploitation of labor that would have been impossible without the Hukou system.

Unlike Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, China welcomed foreign direct investment with open arms, and capital began flowing into the country on a huge scale. With China's entry into the WTO in 2001, all companies were forced to reduce labor costs and social security contributions. The restructuring sealed the fate of hundreds of millions of farmers converted into the proletarians of globalization. The Hukou system would be refined to keep hundreds of millions of workers in absolute marginalization. The fuel of the China industrial revolution and neoliberal globalization has name: Nong Gong Min.

However, although the total number of Nong Min Gong has increased steadily over the past decades, the growth rate has declined significantly over the past five years (from 5.5% in 2010 to just 1.9% in 2014) as a result of their marginalization and growing rural poverty. The Nong Gong Min have no ability to self-reproduce.

And apparently, in the same way that there was a direct relationship between high rates of economic growth and the growth of Nong Min Gong, also seems to be a direct link between the Chinese loss of competitiveness (and economic slowdown) and the exhaustion of Nong Min Gong suplay.

According to a weighted index that includes 7 key growth sectors (synthetic index), Chinese GDP, not only does not grow at the pace announce by Chinese state institutions but in 2015 it has been negative. That is, the Chinese giant has entered recession.

International capital and Chinese state have worked closely together to transform hundreds of millions of Chinese peasants in flexible, submissive, redundant and cheap proletariat, at a speed and on a scale unprecedented in world history. The resounding success of 'made in China "over the last two decades is the story of rural migrant workers exploited by a below subsistence wage to produce at the lowest price. The "China price"

The current system is a capitalist adaptation of the Hukou of the Maoist era. The Hukou is a kind of family book or residence documentation. Originally the system was attempting to fix the rural population in their villages to avoid the cities overpopulation. Any inhabitant of a city without urban Hukou was immediately expedited by the authorities to their village of residence.

Broadly speaking, the history of the Hukou system can be conceptualized in three stages.

1. Records of residence had been used by the Chinese authorities for thousands of years to manage taxes and controlling migration. The origins of the Hukou system were in the registration system of the population (baojia) that began in the eleventh century. Its main objectives were compliance with the law and civilian control. Each BAO included ten JIAS, while each Jia brought together ten households. The Bao and Jia chiefs were responsible of local law enforcement, taxation, security and civil works. In more modern times, the population register was also used by the Kuomintang and the Japanese in the occupied areas.

2. The Hukou was formally introduced by the communist government in 1958 in response to the shortage of cereals, whose cause was attributed to rural-urban migration. The system was designed to facilitate three main programs: government welfare and resource distribution, internal migration control, and criminal surveillance. Every town and city issued its own internal passport or Hukou, giving residents access to welfare services in that jurisdiction. The Hukou was hereditary so children whose parents had a rural Hukou also had a rural Hukou no matter where they were born.

Between 1950 and 1970 the Communist Party used Hukou registration to implement the agricultural collectivism in rural areas of China, while it was rapidly industrializing urban China. Farmers had to sell their cereals and other crops at low prices to the state, which it rationed to urban workers. The peasant migration to the cities was tightly controlled by the Hukou system. Yet there was a considerable increase in urban population. The Communist Party responded by initiating several campaigns of relocation of urban workers who were sent to develop sparsely populated rural areas.

3. The transformation of the maoists Hukou to capitalist Hukou began in 1985 when a new system of temporary residence permits introduced by the Ministry of Public Security was established. This allowed the rural Hukou holders to migrate to urban areas without having to formalize a previous employment contract which was required under the previous system. And so it began what is often described as one of the biggest human migrations of all time, as millions of young men and women from the countryside filled factories and construction sites under construction in the coastal cities of China. In many cities, such as Shenzhen and Dongguan, the population of migrant workers quickly outgrew the local urban population.

The Hukou has undergone a series of reforms or improvements to suit the precise needs of the industry. It has evolved into a finely tuned system of discrimination and institutional control. Reforms decentralized the Hukou to local governments to improve and better adapt the system to the interests of transnational capital investment. The improved Hukou system has been the linchpin of the enormous profits of Appel, Cisco, IBM, HP, Samsung, Adidas, Toyota, Microsoft, etc.

In Shenzhen, the Hukou system is specially designed to maintain absolute control of labor. When Nong Min Gong are hired by companies they must be registered by the local labor office as temporary workers, after payment of a fee to the city. Companies must obtaine from the Public Security Bureau a certificate of temporary residence registration, and they must notify to the Local Police Office the registering of a temporary hukou. The temporary residence is only for one year and must be renewed annually.

In many cities, the rich or educated migrants can easily convert their residence Hukou. Since the mid-1990s, some local governments have the ability to sell local Hukou to investors. In some cities it was possible to obtain a local Hukou buying a property from a certain value. Like everything in China, this discriminatory practice has been dubbed "talent exchange and investment for a Hukou" and is generalizing across China.

Some cities issue "blue stamp" Hukou (to distinguish from the official red stamp Hukou), a kind of transient urban Hukou that needs special qualifications (entry conditions) in order to allow the entry of precise groups of people, a kind quasi-urban Hukou entitling to a sort of partial citizenship.

In Beijing, there is a "very competitive" Hukou system, which includes no less than eighteen different categories of transfer of Hukou based on what the applicant can offer to the city (workers in the field of science and technology, students returning after studying abroad, financial, experts, etc.)

In Shanghai, there are four types of cards that target different groups of migrants and grant different privileges. The "talent residence permit" is designed to attract highly skilled and educated professionals. There is a second type of card for foreigners or "overseas Chinese" working in Shanghai, while the third is for migrants who have a permanent job or running a local business and have a current address. For immigrants who do not meet the above criteria are given a renewable "temporary residence card" (Linshi juzhu Zheng) issued from time to time, that usually grant legal residence for a period of six months and gives access to minimum social services.

Nong Min Gong (rural migrant worker) has a specific meaning in China; It refers to urban workers with rural Hukou. Although these workers are working in urban jobs legally they are not considered urban workers. The category of Nong Min Gong is not temporary but permanent and discriminatory. As "rural" they have not right to "urban" social services (education of their children, pensions, unemployment help, public housing, public health, disability insurance, etc.) and any rights that are available for other urban residents. In legal terms, the Nong Min Gong are treated as part (or as an extension) of the population with rural Hukou, despite working and living in urban areas during most of the year, often for many years. They have to endure all kinds of discrimination, including discrimination in employment, wage discrimination, discrimination in social services, discrimination in education, etc.

Such social isolation drives to social discrimination. They are blamed as invaders and a long list of problems (responsible for traffic jams, high population density and crime in general) are attributed to them. The stereotype of Nong Min Gong is that they are "uneducated, ignorant, dirty and prone to crime".

The weight of the Nong Min Gong in Chinese economy is huge. They represent 79.8% of all employed in urban construction, 68.2% of jobs in electronics manufacturing and 58% of the workers of the restoration sector.

Being Chinese the law consider them immigrants in their own country. But unlike immigrants in Europe or the US, they are treated without ateny contemplations since they are supposed a category of "tourists" temporarily in the city where they work. That is, they are undocumented workers in their own country. They have no right to housing since it is supposed they already have permanent residence in their village. They are always living "provisionally" in crowded dormitories in the same factories or buildings where they work or in rental buildings. They can not educate their children as they are supposed to already have school places in their villages of origin, etc. In fact, the Hukou system divides Chinese society into two classes. Few urban residents socialize with Nong Min Gong (the term is pejorative) and intermarriage are considered unwise.

They have no right to compensation , unemployment benefits, to severances insurance, sickness insurance, public health, etc. Their low wages are always below the subsistence level since it is assumed that their subsistence and reproduction takes place in their home villages.

When the financial crisis broke in 2008, export centers experienced a nosedive. This was accompanied by mass layoffs, widespread arrears or unpaid wages and factory closures. In late 2008, more than 62,000 factories in Guangdong province had closed and 26 million Nong Min Gong were fired and forced by urban authorities to return to their villages of origin.

As a "paperless" they must avoid any conflict with their bosses to avoid being deported back to their home villages. Public discourse often refers to migrant workers as people who deviate from the "norm" and therefore need to be corrected and educated.

The Hukou system is also a sophisticated instrument of social and political control since it allows tracking people who are politically dubious to party standards. Technology has made it easier to apply the Hukou system because now the police have a national database of Hukou official records . This has been possible thanks to the computerization of the 1990s, as well as greater cooperation between the different regional police authorities.

In Shanghai and Shenzhen a new temporary residence card as mandatory identification for all migrants to stay in Guangdong for more than a month was adopted in 2006. The card, which is the size of a credit card contains a chip that stores personal information of the subject, including the employment status, credit history, criminal records and even family planning folder. The system has spread to most Chinese cities.

In 2002, more than 30,000 police stations in the country had computerized the Hukou management and the Hukou records of 650 million people could be consulted through a single national computer network.

Based on the files of Hukou, police maintains a confidential list of suspected persons (Zhongdian renkou 重点 人口) in each community (usually about five percent of the total population of the community) that are specially monitored and controlled.

Random and humiliating checks of identity documents in the street, especially near railway stations, or after midnight in residential units migrants, and detention and forced repatriation of people without permits, is a common police practice. Eventually though the raids are still done on a regular basis, they are done more discreetly in big cities like Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai, Wuhan, and in the smaller cities of the Pearl River Delta.

Undocumented migrants who are caught can be "fined, undergo a period of detention, be subject to forced repatriation, criminal prosecution and even prison sentences.

There was a set of laws on "Custody and Repatriation" establishing detention centers in different cities for the custody and repatriation of illegal immigrants Nong Gong Min. The administrative procedure of Custody and Repatriation was established in 1982. Under this procedure the police could detain any Chinese citizen without a residence permit (Hukou) or temporary housing permit (Zanzhu Zheng) in a Custody and Repatriation Center, and return them forcibly to their place of origin. Conditions in Custody and Repatriation Centers were often worse than prisons or reeducation camps (including beatings and prolonged detentions without trial). Sometimes the police used the system to kidnap Nong Min Gong and extort their families arguing maintenance and repatriation expenses. The system was abolished in 2003 after the death of Sun Zhigang, a migrant worker who died of mistreatment during his detention in the Custody and Repatriation Center of Guangzhou. Sun Zhigang, the victim of 27 years turned out to be a college graduate from the University of Science and Technology, Wuhan and his case sparked a huge viral campaign on social networks (that would be the last), hence the gesture of the Chinese authorities.

In thirty years of annual GDP growth averaging 10%, all employment growth has been outside the formal sector, which means that an increasing percentage of Chinese workers are not covered by the country labor laws, and their wages , benefits and working conditions are not caught by the Chinese official labor statistics. (Misleading Chinese Legal and Statistical Categories: Labor, Individual Entities, and Private Enterprises)

Employers often contract private employment agencies avoiding to directly hire Nong Min Gong workers so that they are working without a contract most of the time or with very temporary contracts. Very rarely they obtain long term employment contracts.

According to the recommendations of Human Resources Managers (HRM) the Nong Min Gong should be relegated to the three 'D' (difficult, dirty and dangerous). The same state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the Chinese big transnational corporations often recruit (under subcontracts) many Nong Min Gong for hard, dirty and dangerous jobs.

The Nong Gong Min of the employment agencies are usually paid based on the minimum wage level in his native village and not on basis of the minimum wage of the city where they work. Some companies try to justify this by saying that rural workers need not be paid so much because they have other sources of income from the land in his native Hukou, and have fewer expenses because their families are in rural areas.

Much of migrants are illegal immigrants "undocumented" ie without Hukou or temporary residence card. Because of "paperless" nature there is no official estimate of the number of such migrants, although it is estimated that in several cities their number would be between 20 and 60% of the population, ie over 100 million of people.

In the Economic Survey of China 2010 of the OECD it is noted that illegal immigrants are "probably" more than 40% of the total workforce in urban centers. These are the lowest paid of all. They are the real pariahs of globalization.

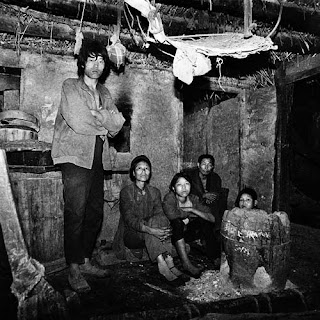

In many villages, only the elderly and children remain because the working agwie generations are in search of employment, providing much of the cheap labor that has made China the most formidable competitor of the export-oriented manufacturing worl, . With employers of migrant labor paying low wages that do not cover the cost of its reproduction.

In China remains a peculiar system of rural land tenure, established in the 1980s, which prevents the sale of land, which has prevented the mass expropriation of the means of livelihood of farmers. This system has so far avoided the social instability which would have meant the mass alignment of 600 million people from their traditional means of livelihood.

The post Maoist "household responsibility system" set aside the role of the Commune as organizer of agricultural production, making the peasant household the basic unit of production.

The abolition of the Maoist rural collectivism began with experiments in the allocation of land to small production households in Sichuan and Anhui in 1978 (the "household responsibility system"). It was a time of struggle between the pro-capitalist fraction and the Maoist fraction and the capitalist fraction seeking to win the peasant masses. The commune system was extinct in 1983; an increase of 50 percent grain prices (paid by the state) and a large increase in fertilizer subsidies led to an annual 9% increase in agricultural production which increased rural incomes by 98.4% in the same time span: it was "the highest rate of reduction of rural poverty in world history."

Achieved the political objective, the state turned to the economic objective. The path to rapid industrialization by China's opening to transnational capital. But to produce cheap labor willing to emigrate needed the re-impoverishment of peasantry. This was done in two stages. First, a fundamental change in the tax system freed the central government of funding the administrative costs of the authorities at lower levels. From now on local governments adjusted their spending and investment within the limits of the taxes and charges that they may apply to residents within its jurisdiction.

In a second stage, local administrative bodies now converted into monstrous bodies of corporate management, began to exploit the residents under its jurisdiction with a growing number of fees and charges to feed its own continuous expansion. Offices responsible for seed, fertilizer, electricity, irrigation and flood control, all raised the price of their services to an extent that in many cases the farms were ruined and lost the recent profits from the era of "household responsibility system".

Currently the land is still regarded as a public good and state prevents the sale of farmland, which has prevented, so far, the expropriation of livelihoods of farmers. The system of land tenure established in the 1980s has served the wider interests of capital because it has not only avoided the social instability associated with huge landless masses, but has subsidized capital employing Nong Min Gong which reproductive capacity is assumed to be produced in their hometowns.

Despite the rapid growth of the Chinese economy in recent decades, more than 482 million people - 36% of the total population - live on less than $ 2 a day. The 85% of China's poor live in rural areas. In many villages, only the elderly and children remain.

Although they do the same work, the wages of Nong Min Gong are much lower than that of urban residents.

Moreover, wages of workers with urban Hukou increased year after year, while Nong Gong Min real wages declined. The Nong Min Gong work much longer hours than workers with urban Hukou. In 2006, 48.2% of workers with urban Hukou worked 40 hours per week, while 47.4% of Nong Min Gong worked more than 48 hours per week. In addition, the salaries of Nong Min Gong workers always suffer deductions and with any excuse payment is delayed without justification. Employers always make unequal treatment between workers with urban Hukou and Nong Min Gong . The total number of delayed payment of wages to Nong Min Gong in 2002 reached nearly 30 billion yuan.

All official statistics on wages Nong Min Gong are inflated because between 70 and 80% of them work in the informal sector where wage insecurity is absolute.

In addition, the Nong Min Gong workers lack at all of the "invisible income" that benefit those with urban Hukou, including housing allowance, education allowance, health insurance, accident insurance, unemployment insurance, etc.

Official data from 2004 showed that 145 million workers had no formal contract (the figure should be much higher). The labor market in China is notorious for bad working conditions, unpaid wages, low wages, forced labor and other forms of abuse. All this is reflected in the unprecedented increase i n the Gini coefficient (which measures inequality from "0" - equality - to "100" - one person owns everything-) of 0.16 in 1978 to 47.3 in 2006 and 61 in 2010. The share of wages in China's GDP has been steadily declining, falling to 36.7% in 2005.

For large transnational corporations one of the main attractions to settle in Chinese territory is the existence of Hukou. Multinational companies take advantage of the anti-union climate, lack of knoledge of workers of their rights and the unwillingness of the Chinese government to address the systematic abuse of Nong Min Gong.

CEOs and specialists and managers in human resources (HRM) of large transnational corporations soon realized the enormous possibilities of the Hukou system for your globalists plans. The Hukou would become the pivot of the monopolist globalization becoming a permanent forced filter for the diabolical proletarianization of hundreds of millions of peasants. Rural migrant workers, the Nong Min Gong are not only the backbone of China's manufacturing sector, but also constitute the fundamental basis of the global supply chain and therefore the pace of the global economy and the Nong Min Gong labor are closely related.

Although slowing growth in China is related to the fall in global aggregate demand caused by the Monopoly Depression, loss of Chinese competitiveness is closely related to the exhaustion of its supply of Nong Min Gong. Less Nong Min Gong less growth.

The School of Management at Royal Holloway University of London produce Working Papers edited with suggestive titles such as: "Prolonged Selection or Extended Flexibility? A case study of Japanese Subsidiaries in China"2012. The author of the paper is Dr. Yu Zheng, Lecturer in Asian Business and International Human Resource Management at that university.

The objective of the research (case study) is to explore the Chinese labor market institutions to improve employment practices of multinationals, particularly subsidiaries of two Japanese consumer electronics sector corporations. The document notes that the Hukou system has important implications for targeting groups of workers in the local labor market.

According to the analysis of the case, the firm hire technicians and specialized personnel "normally" ("internal employment system"), the other employees are recruited through employment agencies (this group is marginalized and excluded from the "internal employment system"of the firm).

The group of plant workers is constituted mainly by Nong Min Gong , with renewable 3 months contracts without guarantees of permanence in the company. During peak season, more than 80% of plant workers were Nong Min Gong who were recruited through a large number of local employment agencies. They perform simplified tasks: welding, assembly, painting and packaging. These workers are imparted minimal training and salary is based largely on its daily production (piecework). After the period of three months of employment these Nong Min Gong return to the labor agencies, the subsidiary of the Japanese multinational thus avoiding paying the social insurance of these workers and other labor costs.

The supply of Nong Min Gong and rotation control of their contracts are a key challenge for companies with foreign investment in China. Local temporary employment agencies play a key rol for recruitment of abundant, flexible and low-wage work. Local labor agencies have connection with regional abor agencies and collect information of rural migrants. Employment agencies also provide specialized training for disciplining Nong Min Gong. These agencies also cover the basic insurance and are responsible for handling complaints of workers, all of which allows subsidiaries of Japanese multinationals outsource these costly management job functions.

As demand for workers increases, the Japanese subsidiary, following the recommendations of local managers, sign long-term contracts with various employment agencies in order to expand the range of origin of migrant workers and prevent the formation of alliances according to their hometown. In the Chinese context, native alliances are common and are a key source of solidarity and integration of workers, which must be avoided at all costs.

Inside the factory prevails personal network rooted in traditional society and this is exploited by manufacturers as a control strategy, taking advantage of the interaction between gender, place of origin and gangsterism.

Their number has continued to increase at the pace of China's industrialization but it seems that finally the goose that lays golden eggs is leaving to put on.

There were about 30 million in 1989. In 2007 it was estimated that they were 136 million. In 2008 there were about 225 million Nong Gong Min, of which more than 80% worked in the informal sector. In 2013 the number had increased to more than 270 million.

According to the annual survey conducted by the National Bureau of Statistics, in 2014 there were 274 million Nong Min Gong , representing about 36% of all workers in China (770 million).

Although the total number of Nong Min Gong has increased steadily over the past decades, the growth rate has declined significantly in the last five years (5.5% in 2010 to just 1.9% 2014). This slowdown is due to the contraction of the working age population in China. Restrictive family planning policies introduced in the 1980s, procreation difficulties because of discrimination and increasing rural poverty, cause fewer and fewer people are entering the labor force and, therefore, it seems likely that the population of Nong Min Gong in China has already reached its zenith.

The gender balance of Nong Min Gong in 2014 was two-thirds of barons by one-third women. The trend is towards an older population. The proportion of workers aged 16 to 30 years old decreased from 42% in 2010 to 34% in 2014, while the proportion of workers over 40 years of age has risen from 34% in 2010 to 43% in 2014.

This slowing trend could be offset if the authorities end up putting into practice plans that aim to transform the Chinese countryside handing it over to large agro-industrial corporations, expelling from rural areas over a hundred million of peasant families (according to the Latin American model).

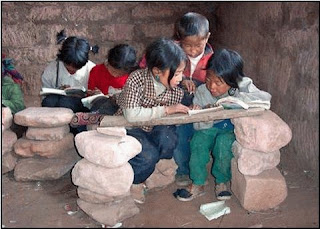

In most cities, the children of Nong Min Gong can not go to school because they do not have a local Hukou. The children of Nong Min Gong are not permitted to enroll in city schools, so they must be separated from their parents and live with grandparents or other relatives, in order to attend school in their hometowns. They are commonly known as "left at home children". There are about 130 million children living in villages without their parents. These rural schools suffer from a maddening lack of funds and consequently of educational quality. Chinese universities have a growing bias against the admission of students from these rural schools. In response to the resulting social problems, 13 newspapers from various regions of China issued a joint call for a campaign for the abolition of the Hukou system (2 March 2010) , but it was silenced in a matter of days.

Public schools do not admit children of Nong Min Gong but they can do that charging high fees (Jiedu). Some have built Nong Min Gong "private" schools for their children, low-cost schools known as "schools of migrant children". Researchers and journalists have found a lot of problems regarding the quality and safety of these schools.

A mass emigration of hundreds of millions of peasants to the cities and the low wages they earn should have led to the emergence of slums and shanty towns on a large scale in the big cities as in India and in general throughout Southeast Asia. The Chinese government has done everything to erase the bad image of its economic miracle. However, the key instrument that has prevented the formation of shanty districts has been the Hukou system by which Nong Min Dong can only stay in cities provisionally. This forces them to reside in the same works or factories where they work, or pile up in rented temporary homes.

The Nong Min Dong not have the freedom to settle permanently any where. They are allowed to remain in dwellings provided by their employers (charging them rent or deductions of their wages) or by renting beds to local owners in dormitory neibourhood (chengzhongcun), provided they have employment and to register with local authorities as employees in transit ( the average living space of Nong Min Dong in Shanghai is 6m2). They must return to their county of origin after a prolonged period of unemployment or retirement - usually after 35 years -. Local authorities are well rid of Nong Min Dong when they are no longer profitable.

http://chuangcn.org/blog/

http://elsalariado.info/2015/02/17/la-situacion-de-la-clase-obrera-en-china-el-sistema-Hukou/

http://www.gongchao.org/en/frontpage

http://economicstudents.com/2014/03/a-brief-history-of-chinas-Hukou-system/

Corrupción interactiva

http://www.chinafile.com/multimedia/infographics/visualizing-chinas-anti-corruption-campaign

http://www.chinafile.com/multimedia/infographics/nongmin-breakdown

http://www2.gsid.nagoya-u.ac.jp/blog/anda/files/2010/06/27_zhao-ling.pdf

https://repository.royalholloway.ac.uk/file/835844b8-dd0a-b735-347c-e206d4e09aef/1/Zheng,%20Y%20working%20paper%201204%20May%202012%20formatted%20version.pdf

http://www.clb.org.hk/content/migrant-workers-and-their-children

Du Runsheng: "For two decades since 1980 there has been almost no real increase in wages of rural migrant workers (Nong Gong Min) in coastal areas despite the rapid growth of China as a major economic linchpin of the global economy"

David Coates (theoretical netizen new capitalism): "Modern globalization is a process based less on the proliferation of computers than in the proliferation of proletarians"

Kam Wing Chan: "Alarmingly, the gap between the total population living in cities and the number of those with urban residence registration (urban Hukou) has increased as the country progressed. That gap represents the expansion of many people living in the city but not belonging to the city (Nong Min Gong)"

There are an estimated 274 million rural migrant workers in China, representing more than one third of the working population. Migrant workers have been the engine of spectacular economic growth in China over the past three decades.

Migrant rural workers - Nong Min Gong -, are workers with a rural Hukou (household registration) who are employed in a place of urban work. However, many of them have not even been born in rural areas. Many have grown or even born in the city but according to the Hukou system they retain the stigma of Nong Min Gong from their parents.

Chinese State and multinational capital have contributed to keeping this great mass of proletarians as marginalized persons subject to institutionalized discrimination, as if they were undocumented foreigners in their own country.

Chinese capitalism has created a system of production relations that is more efficient and brutal than most. The formidable escalation of China as the most competitive industrial power in the world, has been largely achieved thanks to a highly efficient exploitation of labor that would have been impossible without the Hukou system.

Unlike Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, China welcomed foreign direct investment with open arms, and capital began flowing into the country on a huge scale. With China's entry into the WTO in 2001, all companies were forced to reduce labor costs and social security contributions. The restructuring sealed the fate of hundreds of millions of farmers converted into the proletarians of globalization. The Hukou system would be refined to keep hundreds of millions of workers in absolute marginalization. The fuel of the China industrial revolution and neoliberal globalization has name: Nong Gong Min.

However, although the total number of Nong Min Gong has increased steadily over the past decades, the growth rate has declined significantly over the past five years (from 5.5% in 2010 to just 1.9% in 2014) as a result of their marginalization and growing rural poverty. The Nong Gong Min have no ability to self-reproduce.

And apparently, in the same way that there was a direct relationship between high rates of economic growth and the growth of Nong Min Gong, also seems to be a direct link between the Chinese loss of competitiveness (and economic slowdown) and the exhaustion of Nong Min Gong suplay.

According to a weighted index that includes 7 key growth sectors (synthetic index), Chinese GDP, not only does not grow at the pace announce by Chinese state institutions but in 2015 it has been negative. That is, the Chinese giant has entered recession.

Hukou

International capital and Chinese state have worked closely together to transform hundreds of millions of Chinese peasants in flexible, submissive, redundant and cheap proletariat, at a speed and on a scale unprecedented in world history. The resounding success of 'made in China "over the last two decades is the story of rural migrant workers exploited by a below subsistence wage to produce at the lowest price. The "China price"

From maoist Hukou to capitalist Hukou

The current system is a capitalist adaptation of the Hukou of the Maoist era. The Hukou is a kind of family book or residence documentation. Originally the system was attempting to fix the rural population in their villages to avoid the cities overpopulation. Any inhabitant of a city without urban Hukou was immediately expedited by the authorities to their village of residence.

Broadly speaking, the history of the Hukou system can be conceptualized in three stages.

1. Records of residence had been used by the Chinese authorities for thousands of years to manage taxes and controlling migration. The origins of the Hukou system were in the registration system of the population (baojia) that began in the eleventh century. Its main objectives were compliance with the law and civilian control. Each BAO included ten JIAS, while each Jia brought together ten households. The Bao and Jia chiefs were responsible of local law enforcement, taxation, security and civil works. In more modern times, the population register was also used by the Kuomintang and the Japanese in the occupied areas.

2. The Hukou was formally introduced by the communist government in 1958 in response to the shortage of cereals, whose cause was attributed to rural-urban migration. The system was designed to facilitate three main programs: government welfare and resource distribution, internal migration control, and criminal surveillance. Every town and city issued its own internal passport or Hukou, giving residents access to welfare services in that jurisdiction. The Hukou was hereditary so children whose parents had a rural Hukou also had a rural Hukou no matter where they were born.

Between 1950 and 1970 the Communist Party used Hukou registration to implement the agricultural collectivism in rural areas of China, while it was rapidly industrializing urban China. Farmers had to sell their cereals and other crops at low prices to the state, which it rationed to urban workers. The peasant migration to the cities was tightly controlled by the Hukou system. Yet there was a considerable increase in urban population. The Communist Party responded by initiating several campaigns of relocation of urban workers who were sent to develop sparsely populated rural areas.

3. The transformation of the maoists Hukou to capitalist Hukou began in 1985 when a new system of temporary residence permits introduced by the Ministry of Public Security was established. This allowed the rural Hukou holders to migrate to urban areas without having to formalize a previous employment contract which was required under the previous system. And so it began what is often described as one of the biggest human migrations of all time, as millions of young men and women from the countryside filled factories and construction sites under construction in the coastal cities of China. In many cities, such as Shenzhen and Dongguan, the population of migrant workers quickly outgrew the local urban population.

The Hukou has undergone a series of reforms or improvements to suit the precise needs of the industry. It has evolved into a finely tuned system of discrimination and institutional control. Reforms decentralized the Hukou to local governments to improve and better adapt the system to the interests of transnational capital investment. The improved Hukou system has been the linchpin of the enormous profits of Appel, Cisco, IBM, HP, Samsung, Adidas, Toyota, Microsoft, etc.

In Shenzhen, the Hukou system is specially designed to maintain absolute control of labor. When Nong Min Gong are hired by companies they must be registered by the local labor office as temporary workers, after payment of a fee to the city. Companies must obtaine from the Public Security Bureau a certificate of temporary residence registration, and they must notify to the Local Police Office the registering of a temporary hukou. The temporary residence is only for one year and must be renewed annually.

In many cities, the rich or educated migrants can easily convert their residence Hukou. Since the mid-1990s, some local governments have the ability to sell local Hukou to investors. In some cities it was possible to obtain a local Hukou buying a property from a certain value. Like everything in China, this discriminatory practice has been dubbed "talent exchange and investment for a Hukou" and is generalizing across China.

Some cities issue "blue stamp" Hukou (to distinguish from the official red stamp Hukou), a kind of transient urban Hukou that needs special qualifications (entry conditions) in order to allow the entry of precise groups of people, a kind quasi-urban Hukou entitling to a sort of partial citizenship.

In Beijing, there is a "very competitive" Hukou system, which includes no less than eighteen different categories of transfer of Hukou based on what the applicant can offer to the city (workers in the field of science and technology, students returning after studying abroad, financial, experts, etc.)

In Shanghai, there are four types of cards that target different groups of migrants and grant different privileges. The "talent residence permit" is designed to attract highly skilled and educated professionals. There is a second type of card for foreigners or "overseas Chinese" working in Shanghai, while the third is for migrants who have a permanent job or running a local business and have a current address. For immigrants who do not meet the above criteria are given a renewable "temporary residence card" (Linshi juzhu Zheng) issued from time to time, that usually grant legal residence for a period of six months and gives access to minimum social services.

Nong Min Gong

Nong Min Gong (rural migrant worker) has a specific meaning in China; It refers to urban workers with rural Hukou. Although these workers are working in urban jobs legally they are not considered urban workers. The category of Nong Min Gong is not temporary but permanent and discriminatory. As "rural" they have not right to "urban" social services (education of their children, pensions, unemployment help, public housing, public health, disability insurance, etc.) and any rights that are available for other urban residents. In legal terms, the Nong Min Gong are treated as part (or as an extension) of the population with rural Hukou, despite working and living in urban areas during most of the year, often for many years. They have to endure all kinds of discrimination, including discrimination in employment, wage discrimination, discrimination in social services, discrimination in education, etc.

Such social isolation drives to social discrimination. They are blamed as invaders and a long list of problems (responsible for traffic jams, high population density and crime in general) are attributed to them. The stereotype of Nong Min Gong is that they are "uneducated, ignorant, dirty and prone to crime".

The weight of the Nong Min Gong in Chinese economy is huge. They represent 79.8% of all employed in urban construction, 68.2% of jobs in electronics manufacturing and 58% of the workers of the restoration sector.

The Nong Min Gong are the quintessence of job insecurity

Being Chinese the law consider them immigrants in their own country. But unlike immigrants in Europe or the US, they are treated without ateny contemplations since they are supposed a category of "tourists" temporarily in the city where they work. That is, they are undocumented workers in their own country. They have no right to housing since it is supposed they already have permanent residence in their village. They are always living "provisionally" in crowded dormitories in the same factories or buildings where they work or in rental buildings. They can not educate their children as they are supposed to already have school places in their villages of origin, etc. In fact, the Hukou system divides Chinese society into two classes. Few urban residents socialize with Nong Min Gong (the term is pejorative) and intermarriage are considered unwise.

The Nong Min Gong are the quintessence of labor flexibility

They have no right to compensation , unemployment benefits, to severances insurance, sickness insurance, public health, etc. Their low wages are always below the subsistence level since it is assumed that their subsistence and reproduction takes place in their home villages.

When the financial crisis broke in 2008, export centers experienced a nosedive. This was accompanied by mass layoffs, widespread arrears or unpaid wages and factory closures. In late 2008, more than 62,000 factories in Guangdong province had closed and 26 million Nong Min Gong were fired and forced by urban authorities to return to their villages of origin.

The Nong Min Gong are the quintessence of labor submission

As a "paperless" they must avoid any conflict with their bosses to avoid being deported back to their home villages. Public discourse often refers to migrant workers as people who deviate from the "norm" and therefore need to be corrected and educated.

Political and social control and Custody Laws and Repatriation

The Hukou system is also a sophisticated instrument of social and political control since it allows tracking people who are politically dubious to party standards. Technology has made it easier to apply the Hukou system because now the police have a national database of Hukou official records . This has been possible thanks to the computerization of the 1990s, as well as greater cooperation between the different regional police authorities.

In Shanghai and Shenzhen a new temporary residence card as mandatory identification for all migrants to stay in Guangdong for more than a month was adopted in 2006. The card, which is the size of a credit card contains a chip that stores personal information of the subject, including the employment status, credit history, criminal records and even family planning folder. The system has spread to most Chinese cities.

In 2002, more than 30,000 police stations in the country had computerized the Hukou management and the Hukou records of 650 million people could be consulted through a single national computer network.

Based on the files of Hukou, police maintains a confidential list of suspected persons (Zhongdian renkou 重点 人口) in each community (usually about five percent of the total population of the community) that are specially monitored and controlled.

Random and humiliating checks of identity documents in the street, especially near railway stations, or after midnight in residential units migrants, and detention and forced repatriation of people without permits, is a common police practice. Eventually though the raids are still done on a regular basis, they are done more discreetly in big cities like Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai, Wuhan, and in the smaller cities of the Pearl River Delta.

Undocumented migrants who are caught can be "fined, undergo a period of detention, be subject to forced repatriation, criminal prosecution and even prison sentences.

There was a set of laws on "Custody and Repatriation" establishing detention centers in different cities for the custody and repatriation of illegal immigrants Nong Gong Min. The administrative procedure of Custody and Repatriation was established in 1982. Under this procedure the police could detain any Chinese citizen without a residence permit (Hukou) or temporary housing permit (Zanzhu Zheng) in a Custody and Repatriation Center, and return them forcibly to their place of origin. Conditions in Custody and Repatriation Centers were often worse than prisons or reeducation camps (including beatings and prolonged detentions without trial). Sometimes the police used the system to kidnap Nong Min Gong and extort their families arguing maintenance and repatriation expenses. The system was abolished in 2003 after the death of Sun Zhigang, a migrant worker who died of mistreatment during his detention in the Custody and Repatriation Center of Guangzhou. Sun Zhigang, the victim of 27 years turned out to be a college graduate from the University of Science and Technology, Wuhan and his case sparked a huge viral campaign on social networks (that would be the last), hence the gesture of the Chinese authorities.

Absence of contracts or temporary contracts

In thirty years of annual GDP growth averaging 10%, all employment growth has been outside the formal sector, which means that an increasing percentage of Chinese workers are not covered by the country labor laws, and their wages , benefits and working conditions are not caught by the Chinese official labor statistics. (Misleading Chinese Legal and Statistical Categories: Labor, Individual Entities, and Private Enterprises)

Employers often contract private employment agencies avoiding to directly hire Nong Min Gong workers so that they are working without a contract most of the time or with very temporary contracts. Very rarely they obtain long term employment contracts.

According to the recommendations of Human Resources Managers (HRM) the Nong Min Gong should be relegated to the three 'D' (difficult, dirty and dangerous). The same state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the Chinese big transnational corporations often recruit (under subcontracts) many Nong Min Gong for hard, dirty and dangerous jobs.

The Nong Gong Min of the employment agencies are usually paid based on the minimum wage level in his native village and not on basis of the minimum wage of the city where they work. Some companies try to justify this by saying that rural workers need not be paid so much because they have other sources of income from the land in his native Hukou, and have fewer expenses because their families are in rural areas.

Much of migrants are illegal immigrants "undocumented" ie without Hukou or temporary residence card. Because of "paperless" nature there is no official estimate of the number of such migrants, although it is estimated that in several cities their number would be between 20 and 60% of the population, ie over 100 million of people.

In the Economic Survey of China 2010 of the OECD it is noted that illegal immigrants are "probably" more than 40% of the total workforce in urban centers. These are the lowest paid of all. They are the real pariahs of globalization.

Impoverish the villages to encourage emigration

In many villages, only the elderly and children remain because the working agwie generations are in search of employment, providing much of the cheap labor that has made China the most formidable competitor of the export-oriented manufacturing worl, . With employers of migrant labor paying low wages that do not cover the cost of its reproduction.

In China remains a peculiar system of rural land tenure, established in the 1980s, which prevents the sale of land, which has prevented the mass expropriation of the means of livelihood of farmers. This system has so far avoided the social instability which would have meant the mass alignment of 600 million people from their traditional means of livelihood.

The post Maoist "household responsibility system" set aside the role of the Commune as organizer of agricultural production, making the peasant household the basic unit of production.

The abolition of the Maoist rural collectivism began with experiments in the allocation of land to small production households in Sichuan and Anhui in 1978 (the "household responsibility system"). It was a time of struggle between the pro-capitalist fraction and the Maoist fraction and the capitalist fraction seeking to win the peasant masses. The commune system was extinct in 1983; an increase of 50 percent grain prices (paid by the state) and a large increase in fertilizer subsidies led to an annual 9% increase in agricultural production which increased rural incomes by 98.4% in the same time span: it was "the highest rate of reduction of rural poverty in world history."

Achieved the political objective, the state turned to the economic objective. The path to rapid industrialization by China's opening to transnational capital. But to produce cheap labor willing to emigrate needed the re-impoverishment of peasantry. This was done in two stages. First, a fundamental change in the tax system freed the central government of funding the administrative costs of the authorities at lower levels. From now on local governments adjusted their spending and investment within the limits of the taxes and charges that they may apply to residents within its jurisdiction.

In a second stage, local administrative bodies now converted into monstrous bodies of corporate management, began to exploit the residents under its jurisdiction with a growing number of fees and charges to feed its own continuous expansion. Offices responsible for seed, fertilizer, electricity, irrigation and flood control, all raised the price of their services to an extent that in many cases the farms were ruined and lost the recent profits from the era of "household responsibility system".

Currently the land is still regarded as a public good and state prevents the sale of farmland, which has prevented, so far, the expropriation of livelihoods of farmers. The system of land tenure established in the 1980s has served the wider interests of capital because it has not only avoided the social instability associated with huge landless masses, but has subsidized capital employing Nong Min Gong which reproductive capacity is assumed to be produced in their hometowns.

Despite the rapid growth of the Chinese economy in recent decades, more than 482 million people - 36% of the total population - live on less than $ 2 a day. The 85% of China's poor live in rural areas. In many villages, only the elderly and children remain.

Nong Min Gong wages

Although they do the same work, the wages of Nong Min Gong are much lower than that of urban residents.

Moreover, wages of workers with urban Hukou increased year after year, while Nong Gong Min real wages declined. The Nong Min Gong work much longer hours than workers with urban Hukou. In 2006, 48.2% of workers with urban Hukou worked 40 hours per week, while 47.4% of Nong Min Gong worked more than 48 hours per week. In addition, the salaries of Nong Min Gong workers always suffer deductions and with any excuse payment is delayed without justification. Employers always make unequal treatment between workers with urban Hukou and Nong Min Gong . The total number of delayed payment of wages to Nong Min Gong in 2002 reached nearly 30 billion yuan.

All official statistics on wages Nong Min Gong are inflated because between 70 and 80% of them work in the informal sector where wage insecurity is absolute.

In addition, the Nong Min Gong workers lack at all of the "invisible income" that benefit those with urban Hukou, including housing allowance, education allowance, health insurance, accident insurance, unemployment insurance, etc.

Official data from 2004 showed that 145 million workers had no formal contract (the figure should be much higher). The labor market in China is notorious for bad working conditions, unpaid wages, low wages, forced labor and other forms of abuse. All this is reflected in the unprecedented increase i n the Gini coefficient (which measures inequality from "0" - equality - to "100" - one person owns everything-) of 0.16 in 1978 to 47.3 in 2006 and 61 in 2010. The share of wages in China's GDP has been steadily declining, falling to 36.7% in 2005.

TNC, Nong Min Gong and employment agencies

For large transnational corporations one of the main attractions to settle in Chinese territory is the existence of Hukou. Multinational companies take advantage of the anti-union climate, lack of knoledge of workers of their rights and the unwillingness of the Chinese government to address the systematic abuse of Nong Min Gong.

CEOs and specialists and managers in human resources (HRM) of large transnational corporations soon realized the enormous possibilities of the Hukou system for your globalists plans. The Hukou would become the pivot of the monopolist globalization becoming a permanent forced filter for the diabolical proletarianization of hundreds of millions of peasants. Rural migrant workers, the Nong Min Gong are not only the backbone of China's manufacturing sector, but also constitute the fundamental basis of the global supply chain and therefore the pace of the global economy and the Nong Min Gong labor are closely related.

Although slowing growth in China is related to the fall in global aggregate demand caused by the Monopoly Depression, loss of Chinese competitiveness is closely related to the exhaustion of its supply of Nong Min Gong. Less Nong Min Gong less growth.

The School of Management at Royal Holloway University of London produce Working Papers edited with suggestive titles such as: "Prolonged Selection or Extended Flexibility? A case study of Japanese Subsidiaries in China"2012. The author of the paper is Dr. Yu Zheng, Lecturer in Asian Business and International Human Resource Management at that university.

The objective of the research (case study) is to explore the Chinese labor market institutions to improve employment practices of multinationals, particularly subsidiaries of two Japanese consumer electronics sector corporations. The document notes that the Hukou system has important implications for targeting groups of workers in the local labor market.

According to the analysis of the case, the firm hire technicians and specialized personnel "normally" ("internal employment system"), the other employees are recruited through employment agencies (this group is marginalized and excluded from the "internal employment system"of the firm).

The group of plant workers is constituted mainly by Nong Min Gong , with renewable 3 months contracts without guarantees of permanence in the company. During peak season, more than 80% of plant workers were Nong Min Gong who were recruited through a large number of local employment agencies. They perform simplified tasks: welding, assembly, painting and packaging. These workers are imparted minimal training and salary is based largely on its daily production (piecework). After the period of three months of employment these Nong Min Gong return to the labor agencies, the subsidiary of the Japanese multinational thus avoiding paying the social insurance of these workers and other labor costs.

The supply of Nong Min Gong and rotation control of their contracts are a key challenge for companies with foreign investment in China. Local temporary employment agencies play a key rol for recruitment of abundant, flexible and low-wage work. Local labor agencies have connection with regional abor agencies and collect information of rural migrants. Employment agencies also provide specialized training for disciplining Nong Min Gong. These agencies also cover the basic insurance and are responsible for handling complaints of workers, all of which allows subsidiaries of Japanese multinationals outsource these costly management job functions.

As demand for workers increases, the Japanese subsidiary, following the recommendations of local managers, sign long-term contracts with various employment agencies in order to expand the range of origin of migrant workers and prevent the formation of alliances according to their hometown. In the Chinese context, native alliances are common and are a key source of solidarity and integration of workers, which must be avoided at all costs.

Inside the factory prevails personal network rooted in traditional society and this is exploited by manufacturers as a control strategy, taking advantage of the interaction between gender, place of origin and gangsterism.

Nong Min Gong number

Their number has continued to increase at the pace of China's industrialization but it seems that finally the goose that lays golden eggs is leaving to put on.

There were about 30 million in 1989. In 2007 it was estimated that they were 136 million. In 2008 there were about 225 million Nong Gong Min, of which more than 80% worked in the informal sector. In 2013 the number had increased to more than 270 million.

According to the annual survey conducted by the National Bureau of Statistics, in 2014 there were 274 million Nong Min Gong , representing about 36% of all workers in China (770 million).

Although the total number of Nong Min Gong has increased steadily over the past decades, the growth rate has declined significantly in the last five years (5.5% in 2010 to just 1.9% 2014). This slowdown is due to the contraction of the working age population in China. Restrictive family planning policies introduced in the 1980s, procreation difficulties because of discrimination and increasing rural poverty, cause fewer and fewer people are entering the labor force and, therefore, it seems likely that the population of Nong Min Gong in China has already reached its zenith.

The gender balance of Nong Min Gong in 2014 was two-thirds of barons by one-third women. The trend is towards an older population. The proportion of workers aged 16 to 30 years old decreased from 42% in 2010 to 34% in 2014, while the proportion of workers over 40 years of age has risen from 34% in 2010 to 43% in 2014.

This slowing trend could be offset if the authorities end up putting into practice plans that aim to transform the Chinese countryside handing it over to large agro-industrial corporations, expelling from rural areas over a hundred million of peasant families (according to the Latin American model).

Nong Min Gong children

In most cities, the children of Nong Min Gong can not go to school because they do not have a local Hukou. The children of Nong Min Gong are not permitted to enroll in city schools, so they must be separated from their parents and live with grandparents or other relatives, in order to attend school in their hometowns. They are commonly known as "left at home children". There are about 130 million children living in villages without their parents. These rural schools suffer from a maddening lack of funds and consequently of educational quality. Chinese universities have a growing bias against the admission of students from these rural schools. In response to the resulting social problems, 13 newspapers from various regions of China issued a joint call for a campaign for the abolition of the Hukou system (2 March 2010) , but it was silenced in a matter of days.

Public schools do not admit children of Nong Min Gong but they can do that charging high fees (Jiedu). Some have built Nong Min Gong "private" schools for their children, low-cost schools known as "schools of migrant children". Researchers and journalists have found a lot of problems regarding the quality and safety of these schools.

Absence of slums or shantytowns

A mass emigration of hundreds of millions of peasants to the cities and the low wages they earn should have led to the emergence of slums and shanty towns on a large scale in the big cities as in India and in general throughout Southeast Asia. The Chinese government has done everything to erase the bad image of its economic miracle. However, the key instrument that has prevented the formation of shanty districts has been the Hukou system by which Nong Min Dong can only stay in cities provisionally. This forces them to reside in the same works or factories where they work, or pile up in rented temporary homes.

The Nong Min Dong not have the freedom to settle permanently any where. They are allowed to remain in dwellings provided by their employers (charging them rent or deductions of their wages) or by renting beds to local owners in dormitory neibourhood (chengzhongcun), provided they have employment and to register with local authorities as employees in transit ( the average living space of Nong Min Dong in Shanghai is 6m2). They must return to their county of origin after a prolonged period of unemployment or retirement - usually after 35 years -. Local authorities are well rid of Nong Min Dong when they are no longer profitable.

Links

http://chuangcn.org/blog/

http://elsalariado.info/2015/02/17/la-situacion-de-la-clase-obrera-en-china-el-sistema-Hukou/

http://www.gongchao.org/en/frontpage

http://economicstudents.com/2014/03/a-brief-history-of-chinas-Hukou-system/

Corrupción interactiva

http://www.chinafile.com/multimedia/infographics/visualizing-chinas-anti-corruption-campaign

http://www.chinafile.com/multimedia/infographics/nongmin-breakdown

http://www2.gsid.nagoya-u.ac.jp/blog/anda/files/2010/06/27_zhao-ling.pdf

https://repository.royalholloway.ac.uk/file/835844b8-dd0a-b735-347c-e206d4e09aef/1/Zheng,%20Y%20working%20paper%201204%20May%202012%20formatted%20version.pdf

http://www.clb.org.hk/content/migrant-workers-and-their-children